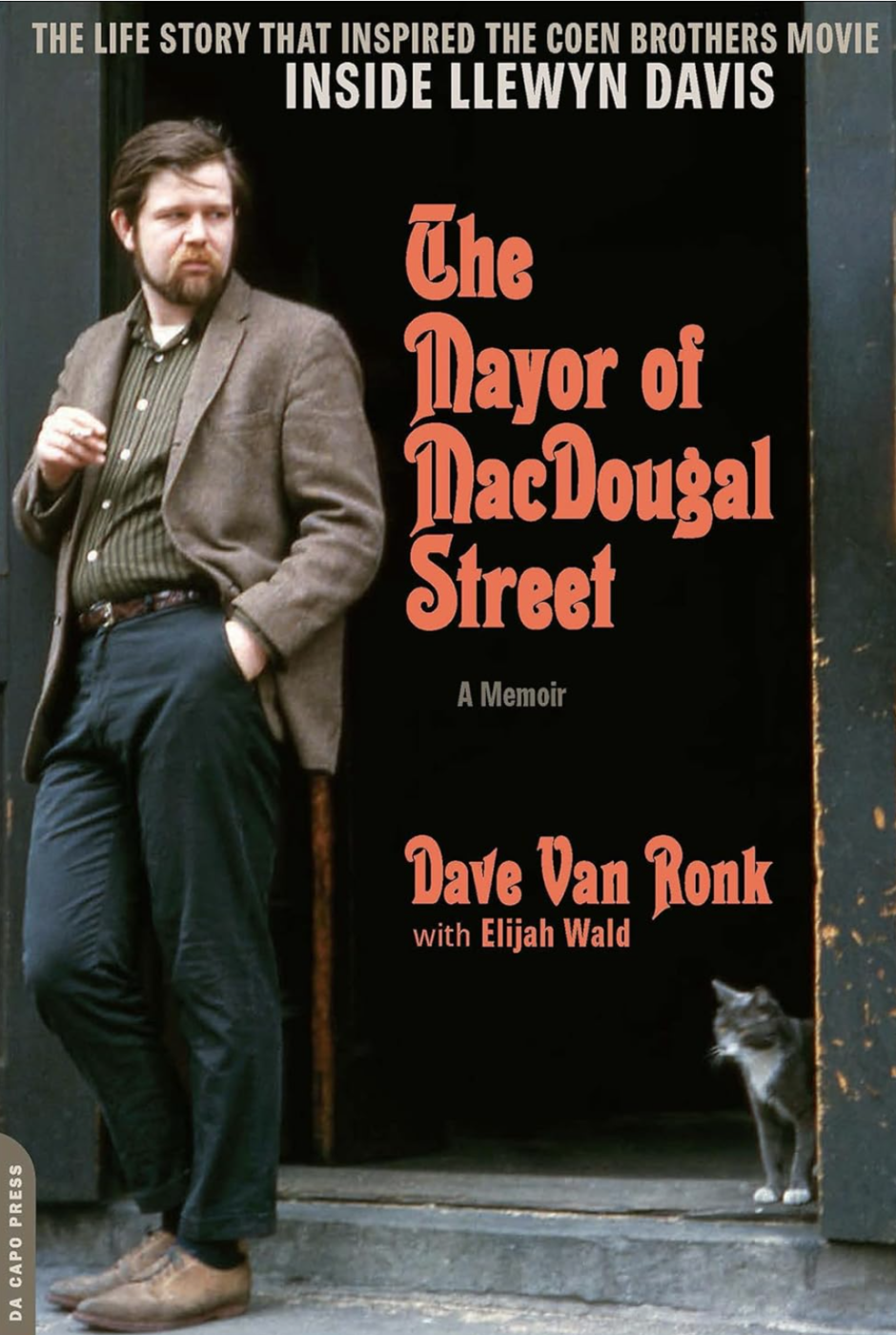

The Mayor of MacDougal Street by Dave van Ronk and Elijah Wald

From My Notion Template

The Book in 3 Sentences

- A wonderful memoir by legitimate legend Dave van Ronk – this book is a perfect long term view of the Greenwich village music phenomenon of the late 1950s and early 1960s written by it’s central participant. Van Ronk wasn’t it’s most well known participant, but he was the most connected and well situated for every event that took place. He provided context and perspective to every other history every written and every anecdote every spun about that time and place.

- Musically he was concerned with “mastery” in the modern use of the term (which expressed itself as professionalism) and was enough of a stand up guy to build and maintain the community that helped him, eventually becoming something of a father figure to the newcomers. The book also provided some wonderful time with an interesting musician and observer (which is a wonderful attribute of any biography). Very insightful about the human condition.

- The movie “Inside Llewyn Davis” was sort of based on the atmosphere described in the book though Dave van Ronk was the inverse in terms of personality and stature. For those who haven’t seen the movie the main character is a self absorbed musician who is an odd combination of unfriendly, dependent, charismatic, despised and admired (musically and as a musician). Van Ronk in real life was quite gregarious, charismatic, often providing for others (Bob Dylan crashed at his place for months apparently), a bit more mature than the other folk singers, while being admired both musically and as a musician (he could, and did, teach).

- After listening to a lot of van Ronk’s music most other folk finger pickers sound quite a bit like him, i.e. most players wind up copying him, whether they want to or not.

How I Discovered It

One of the authors of Dylan Goes Electric co wrote this book.

Who Should Read It?

Anyone, and I mean anyone interested in the music or the time period. It’s a nice way to spend time with an engaging personality

Highlights

“Why should I go anywhere?” Dave said of the Village. “I’m already here.”

Whenever you got here, it was better ten years earlier. That’s what people say now, complaining about gentrification. It’s what they said twenty years ago, complaining about tourists. It’s what they said forty years ago, complaining about hippie kids.

Once, back in the early sixties, I decided to leave New York. I told Dave I was going to return to Buffalo. He was incredulous and asked why, a question I was somehow unable to answer. “Well,” I managed, “that’s my hometown. That’s where I’m from.” He thought about it, then looked off into the middle distance. “I know a woman,” he said, “who was born in Buchenwald.”

It was not particularly interesting, and by that time I had decided I was going to be a musician or, barring that, some other sort of colorful ne’er-do-well.

My mother had decided that I should learn to play the piano, so I used to have to go to the local Sisters of St. Joseph convent for my lessons, and then every afternoon I had to go to the same convent and practice for an hour after school. I leave it to the reader to imagine how much I hated that. It was the first time I learned how to read music, and I detested the whole experience with such a purple passion that until I was in my thirties, I had no desire to read standard notation or play the piano. At that point I began to notice how much better the piano would have suited my musical tastes, but by then I had been playing guitar for twenty years and had managed to make it into a serviceable substitute.

For the rest of my life I continued to use those big fat barbershop chords, especially when I was working out voicings for guitar arrangements.

We only had one gig, a Christmas party at a German fraternal hall in Ridgewood, Brooklyn. Our pay was all the beer we could drink—I suppose they figured, How much beer can a fourteen-year-old kid drink? I do not recall the answer to that, but I am told that they carried me home like a Yule log.

Then, with the help of a Mel Bay instruction book, I set out to prove Segovia’s dictum that the guitar is the easiest instrument in the world to play badly.

Jack showed me some of the fingerings I would continue to use for the rest of my life. He was of the old orchestral jazz school, the musicians who played nonamplified rhythm guitar in the big bands: “Six notes to a chord, four chords to the bar, no cheating,” as Freddie Green used to say. And he also would sometimes use wraparound thumb bar chords and things like that, which had dropped out of the jazz world when more classical guitar techniques came in.

Though he never put it in those terms, it was ear training. He was making us listen, and after a while, if you really paid attention, you got so you could at least make a pretty good guess as to who was playing every instrument. There are people you can’t fool, people who can tell you, “No, that’s not Ben Webster, that’s Coleman Hawkins,” or “That’s not Pres, that’s Paul Quinichette,” and be right every time, and to do that, you can’t just groove with the music. You have to listen with a focus and an intensity that normal people never use. But we weren’t normal people, we were musicians. To be a musician requires a qualitatively different kind of listening, and that is what he was teaching us.

Never use two notes when one will do. Never use one note when silence will do. The essence of music is punctuated silence.

By this time I had heard and read a good deal about Greenwich Village. The phrase “quaint, old-world charm” kept cropping up, and I had a vivid mental picture of a village of half-timbered Tudor cottages with mullioned windows and thatched roofs, inhabited by bearded, bomb-throwing anarchists, poets, painters, and nymphomaniacs whose ideology was slightly to the left of “whoopee!” Emerging from the subway at the West 4th Street station, I looked around in a state of shock. “Jesus Christ,” I muttered. “It looks just like fucking Brooklyn.”

There is no way I can sort out an exact chronology for this hegira, but it started around 1951 and continued in stages over the course of the next few years. I never officially left home, but I would go over to Manhattan and end up crashing on somebody’s floor overnight, and then it got to be two nights, then three, until eventually I was spending most of my time in Manhattan—though every few days I would make the trek back to Queens to change my underwear and see if I could mooch some money. Gradually these visits grew less frequent, and by the time I was about seventeen, I was living in Manhattan full-time.

In hindsight, both sides had their merits and both took their positions to ridiculous extremes. The modernists were aesthetic Darwinists, arguing that jazz had to progress and that later forms must necessarily be superior to earlier ones. The traditionalists were Platonists, insisting that early jazz was “pure” and that all subsequent developments were dilutions and degenerations. This comic donnybrook dominated jazz criticism for ten or fifteen years, with neither side capable of seeing the strengths of the other, until it finally subsided and died, probably from sheer boredom.

Being an adolescent, I was naturally an absolutist, so as soon as I became aware that this titanic tempest in a teapot was going down, I had to jump one way or the other. As a result, I turned my back on a lot of good music. When I was twelve or thirteen, Charlie Christian was my favorite guitarist, I had amassed a huge collection of the Benny Goodman sextet, and I listened to bebop and modern jazz. By the time I was fifteen or sixteen, I had come to regard all of that music as a sorry devolution from the pure New Orleans style. I was convinced, intellectually and ideologically, that the traditionalists had the better of it, and that led me to a lot of good music, but it also led me away from a lot of good music and toward a lot of truly terrible music. It was an ideological judgment rather than a musical one, and it was stupid.

So I switched over and quickly became one of the worst tenor banjo players on the trad scene. And to be the worst at tenor banjo, you’re really competing, because that’s a fast track.

Thus, with my Vega in hand, I set out to be a professional jazzman. By that time I was already six foot two and weighed about 220 pounds. Six or seven months later, thanks to my devotion to jazz, I weighed 170.

I had never starved before, and I had no idea of the great range of possibilities out there in the world—one of them being starvation.

Those were the waning days of the trad-Dixieland revival. I was “just in time to be too late,” as the song says,

The joke in the early 1960s was that I was the only folksinger in New York who knew how to play a diminished chord, and while that was not quite true, it does indicate what set me apart from a lot of the other people.

Eddie Condon once remarked that when you are a musician, a dozen people might offer to buy you a drink in the course of an evening but nobody ever walks up and says, “Hey, let me stand you to a ham sandwich.” Between starvation and inebriation, it’s a miracle that any of us survived, much less actually learned anything.

My acquaintance with the demon weed dates to around 1954, a halcyon year for vipers.*

As I was rapidly discovering, it is hard work surviving without a steady job. I could usually come up with a floor or a couch to crash on, but food was always a problem. We would have boosting expeditions—I never actually did this myself, but I was certainly party to the proceeds—where a group would go into a supermarket and secrete some small, high-value items such as caviar and potted shrimp about their persons. Then we would go out and shop these things off to our more affluent friends for bags of rice and bulk items that were too big to shoplift.

The sight and sound of all those happily howling petit bourgeois Stalinists offended my assiduously nurtured self-image as a hipster, not to mention my political sensibilities, which had become vehemently IWW-anarchist. They were childish, and nothing bothers a serious-minded eighteen-year-old as much as childishness.

I immediately buttonholed him and asked him to show me what he was doing. That was Tom Paley, who later became a founding member of the New Lost City Ramblers.

Gradually, I improved—we all did, actually. When one of us figured something out, the knowledge would be shared, and our general level of skill rose. It was a combined process of experimentation and theft: you would come up with an idea, and the next thing you knew, all your friends would be playing it, but that was fine because when they came up with an idea, you would be playing it. As Machiavelli used to say, “Things proceed in a circle, and thus the empire is maintained.”

So I cast off my carefully cultivated jazz snobbery and set out to reinvent myself as a fingerpicking guitarist and singer. Like the man said, “Sometimes you have to forget your principles and do what’s right.”

In the 1950s, as for at least the previous two hundred years, we used the word “folk” to describe a process rather than a style. By this definition—to which I still subscribe—folk songs are the musical expression of preliterate or illiterate communities and necessarily pass directly from singer to singer. Flamenco is folk music; Bulgarian vocal ensembles are folk music; African drumming is folk music; and “Barbara Allen” is folk music. Clearly, there is little stylistic similarity here, but all these musics developed through a process of oral repetition that is akin to the game we used to call “whisper.” In whisper, one person writes down a sentence, then whispers it to another, who whispers it to a third, and so on around the room until the last person hears it and again writes it down; and then the two messages are compared, and often turn out to be wildly disparate.

And yet, self-announced folk revivals keep surfacing, just as they have at least since the days of Sir Walter Scott. The impulse behind them is generally romantic and anti-industrial—and, a bit surprisingly, among Anglophones in recent times it has almost always come from politically left of center. (Elsewhere, interest in folkloric traditions has often been found in combination with extreme nationalism of the most right-wing and fascist variety.)

a lot of both the middle-class left-wingers and the workers back in the 1930s were first- or second-generation immigrants, and the folk revival served as a way for them to establish American roots. This was especially true for the Jews. The folk revivalists were at least 50 percent Jewish, and they adopted the music as part of a process of assimilation to the Anglo-American tradition—which itself was largely an artificial construct but nonetheless provided some common ground. (Of course, that rush to assimilate was not limited to Jews, but I think they were more conscious of what they were doing than a lot of other people were.)

(The Industrial Workers of the World—IWW, or “Wobblies”—had done something similar back in the teens, but with the difference that singers like Joe Hill and T-Bone Slim were of the folk and generally set their lyrics to pop melodies or church hymns rather than to anything self-consciously rural or working-class.) It was part of the birth of “proletarian chic”—think about that the next time you slip into your designer jeans.

By 1939 this movement had its nexus in a sort of commune on West 10th Street in Greenwich Village called Almanac House. The residents included at one time or another, Pete Seeger, Alan and Bess Lomax, Woody Guthrie, Lee Hays, Millard Lampell . . . the list is long and impressive. All were songwriters to one degree or another (many collaborations and collective efforts here), but Guthrie was by far the most talented and influential of the lot. Taking pains to conceal his considerable erudition behind a folksy facade, he became a kind of proletarian oracle in the eyes of his singer-song-writer associates, who were, of course, incurable romantics. With Guthrie exercising a very loose artistic hegemony (Seeger and Lampell seem to have done most of the actual work), Almanac House became a kind of song factory, churning out topical, occasional, and protest songs at an unbelievable clip, as well as hosting regular “hootenannies.”

the blacklist damn near killed the folk revival in its tracks. The full extent of the witch hunt is rarely acknowledged even today. Most people believe it affected only public figures—people in government and the entertainment world—but that is completely wrong. Trade unions and the professions in the private sector were all profoundly affected, and for a while no one to the left of Genghis Khan could feel entirely safe. Thousands of people lost their jobs and were harassed by the FBI and threatened by vigilante anti-Communist crusaders. I had to sign a loyalty oath to get a job as a messenger, for chrissake, and I have already mentioned Lenny Glaser being fired from his job as a waiter after the FBI came around and asked the restaurant manager some pointed questions about his political affiliations. The right-wing press—which is to say, almost all of it—was running stories like “How the Reds Control Our Schools,” and the whole country was in a paranoid panic that lasted almost two decades. Leftists and intellectuals were terrorized, many essentially unemployable, not a few in prison, and a couple (the Rosenbergs) executed pour encourager les autres. Thus the cheery atmosphere of the Golden Fifties.

The young CP-ers, called the Labor Youth League or LYL, would be spread out all across the park, five-string banjos and nylon-string guitars in hand, singing what they called “people’s songs.” They were very serious, very innocent, and very young, and except for talking (and singing) a lot about “peace,” their political opinions were generally indistinguishable from those of liberal Democrats. They all seemed to go to Music and Art High School, and their parents all seemed to be dentists.

few of the CP’s older and more politically conscious people were usually on hand as well, and these I found evasive, dishonest, and ignorant. After listening to them recite their catechism, I concluded that however loathsome and psychotic the Red-baiters were, they had got one thing right: the CP was the American arm of Soviet foreign policy, no more, no less. They were stolid organization men, and a revolutionary looking for a home might as well have checked out the Kiwanis or the Boy Scouts.

This was the first I had heard that you had to read anything to be an anarchist. It sounded distinctly unanarchistic.

(In those prelapsarian days, the word “libertarian” was still in the hands of its rightful owners: anarchists, syndicalists, council communists, and suchlike. The mean-spirited, reactionary assholes who are currently dragging it through the mud were not even a blot on the horizon. We should have taken out a copyright.)

He had fought in Spain as well, and came out of that experience an extremely bitter anti-Communist. He was convinced that he had returned alive only because he had been taken prisoner by the Fascists—that otherwise he would have been purged by his more orthodox comrades. (Tom Condit, one of my young cohorts in the league, recalls meeting a couple of people who felt this way, and if we knew two, there must have been quite a few others.)

(At the time we knew Sam as Sam Weiner, which was his alias in the movement. Esther went by their married name, but they pretended that they were just living together, because they were very hard-line anarchists and ashamed to have gone through an official marriage ceremony.)

did very little political material. It did not suit my style, and I never felt that I did it convincingly. I just did not have that kind of voice or that kind of presence. Also, although I am a singer and have always had strong political views, I felt that my politics were no more relevant to my music than they would have been to the work of any other craftsman. Just because you are a cabinetmaker and a leftist, are you supposed to make left-wing cabinets?

in that three-year period from the time of the Berlin uprising through to the time of the Hungarian Revolution, more and more of the dirt from the Kremlin was being exposed. In a way, I almost sympathized with them. I mean, put yourself in their shoes: here you are, you’ve spent thirty or forty years of your life peddling poison that you thought was candy—think what that can do to somebody’s head. On the other hand, we could see what was happening in Eastern Europe, and many of us had also had our share of run-ins with authoritarian, Stalinist die-hards in one group or another, and we knew them for the assholes they were. We of the non-Communist left, whether we were revolutionary socialists or anarchists or whatever the hell we were calling ourselves that week, felt that, as Trotsky once said, between ourselves and the Stalinists there was a river of blood. So even though we had a certain admiration for the singers who had stood up to the Red hunters, when you got right down to it we wanted very little to do with them.*

So in a sense, the justifiable paranoia that was common in some sectors of the folk music field in the 1950s left us pretty much untouched.

Naturally, a lot of us despised the idea of needing an official permit, but it did have one advantage: the rule was that everyone was allowed to sing and play from two until five as long as they had no drums, and that kept out the bongo players. The Village had bongo players up the wazoo, and they would have loved to sit in, and we hated them. So that was some consolation.

As a general thing, there would be six or seven different groups of musicians, most of them over near the arch and the fountain. The Zionists were the most visible, because they had to stake out a large enough area for the dancers, and they would be over by the Sullivan Street side of the square, singing “Hava Nagilah.”* Then there would be the LYL-ers, the Stalinists: someone like Jerry Silverman would be playing guitar, surrounded by all these summer camp kids of the People’s Songs persuasion, and they would be singing old union songs and things they had picked up from Sing Out! Sometimes they would have a hundred people, all singing “Hold the Fort,” and quite a lot of them knew how to sing harmony, so it actually could sound pretty good.

The bluegrassers would be off in another area, led by Roger Sprung, the original citybilly. As far as I know, Roger single-handedly brought Scruggs picking to the city—not just to New York but to any city.

Which is not to say that the greensleevers did not have politics—some did, some did not—but there was a consensus among us that using folk music for political ends was distasteful and insulting to the music.

We were all hanging out together, and if you were any kind of musician, you couldn’t find enough hands to pick all the pockets that were available. So I ended up with a very broad musical base, without even thinking about it, simply because of the range of people I was associating with.

Later on, when the scene got bigger, the niches became more specialized and the different groups didn’t mix as much, which was a real pity. The musical world became segregated, and today people no longer get that broad range of influences.

whether it’s me or Dylan or a jazz trumpeter. You have to start somewhere, and the broader your base, the more options you have.

Of course, to a great extent, it was a generational thing: we thought of them as the old wave and conceived of ourselves as an opposition, as is the way of young Turks in every time and place.*

We were severely limited, however, because much as we might consider ourselves devotees of the true, pure folk styles, there was very little of that music available. Then a marvelous thing happened. Around 1953 Folkways Records put out a six-LP set called the Anthology of American Folk Music, culled from commercial recordings of traditional rural musicians that had been made in the South during the 1920s and ’30s. The Anthology was created by a man named Harry Smith, who was a beatnik eccentric artist, an experimental filmmaker, and a disciple of Aleister Crowley. (When he died in the 1990s, his fellow Satanists held a memorial black mass for him, complete with a virgin on the altar.) Harry had a fantastic collection of 78s, and his idea was to provide an overview of the range of styles being played in rural America at the dawn of recording. That set became our bible.

They say that in the nineteenth-century British Parliament, when a member would begin to quote a classical author in Latin, the entire House would rise in a body and finish the quote along with him. It was like that. The Anthology provided us with a classical education that we all shared in common, whatever our personal differences.

they were trying to recreate the music of the teens and twenties, but what actually happened was that they unwittingly created a new kind of music.

Even when I tried to sound exactly like Leadbelly, I could not do it, so I ended up sounding like Dave Van Ronk.

That kind of passionate attention pays off, in terms of being able to learn songs, play, sing, or whatever one needs to do. I was learning more music, and learning it faster, than I have ever done before or since.

He knew theory, knew how all the chords worked and how to build an arrangement, and he was only too happy to show me or anyone else who asked. I latched onto him, and it was like having coffee with Einstein a few times a week.

The rooms were small and ill lit, very crowded, and insufferably stuffy, and the music would go on until four or five o’clock in the morning. Those Spring Street parties led directly to the opening of the first Village folk music venue, and the beginning of my professional career,

have always had the card luck of Wild Bill Hickok, so in self-defense I started up a small blackjack game in the crew mess room—the point being that if you play by Las Vegas rules and have enough capital to ride out the occasional bad night, the dealer simply cannot lose. On the home journey, I made out like a bandit, and I paid off the S.S. Texan with $1,500 and a six-ounce jar of Dexedrine pills provided in lieu of a gambling debt, not to mention a half kilo of reefer scored off a Panamanian donkey-man for $20 while trundling through the Canal. In short, I was loaded for bear.

In concept and design, it was a tourist trap, selling the clydes (customers) a Greenwich Village that had never existed except in the film Bell, Book and Candle.

The Bizarre opened to the public on August 18, 1957, and the entertainment was no slapdash affair.

Hitching to Chicago was easy. You just stuck out your thumb near the entrance of the Holland Tunnel, headed west, and switched to public transportation when you got to the Illinois suburbs. The main problem was sleep. It was about 900 miles and took roughly 24 hours, depending on how many rides you needed to get there. There were some rest stops on the recently completed Ohio Turnpike, but if the cops caught you sleeping, they would roust you, and when they found that you had no car, they would run you in. You could get thirty days for vagrancy, so it was a good idea to stay awake.

His face had the studied impassiveness of a very bad poker player with a very good hand.

By the mid- to late 1960s, there were folklore centers all over America, and every single one was inspired by Izzy Young.

Not a great living, but those were easier times—otherwise, none of us would have made it through. I knew people who were paying $25 or $30 a month for a two-person apartment. Not a good apartment, but it could be done.

What is more, I always thought Pete was a much better musician than most people appreciated—including most of his fans. He phrases like a sonofabitch, he never overplays, and he dug up so much wonderful material. Whatever our disagreements over the years, I learned a hell of a lot from him.

His masterpiece was “The Ballad of Pete Seeger,” a viciously funny reworking of “The Wreck of the Old 97” that began “They gave him his orders at Party headquarters, / Saying, ‘Pete, you’re way behind the times. / This is not ’38, it is 1957, / There’s a change in that old Party Line.’” It had a couple more verses, ending with a quip about how the People’s Artists were going on with “their noble mission of teaching folksongs to the folk.”

Dick was a friend from the Libertarian League and a fellow sci-fi addict (he was one of a group of sci-fi-reading lefties who called themselves the Fanarchists).

He was quite an unprincipled man, and he did not pay the performers; he would make an exception for someone like Odetta or Josh White, but whoever else was on the bill was doing it for the “exposure” (which, as Utah Phillips points out, is something people die of).

we were the cutting edge of the folk revival—though bear in mind, we were in our late teens and early twenties, and if you do not feel you are the cutting edge at that age, there is something wrong with you. Of course we were the wave of the future—we were twenty-one!

As a general rule, I tried to avoid getting mixed up in this kind of convoluted skullduggery, but ever since I was a teenager, I had been reading about Lautrec and absinthe, Modigliani and absinthe, Swinburne and absinthe—naturally I was dying to find out about Van Ronk and absinthe. Also, there was the sheer joy of conspiracy for its own sake. What can I say? I have always been a hopeless romantic.

As for the folk scene, it was beginning to look as if it might have a future, and me with it. Admittedly, a great deal of my concertizing was still at benefits, a clear case of the famished aiding the starving.

And he had found a song called “Who’ll Buy Your Chickens When I’m Gone,” which he changed to “Who’ll Buy You Ribbons”—not a masterpiece, but it got to be a great point of contention later on when Dylan copped the melody and a couple of lines for “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right.”

He had put his own name on a good many of his arrangements of older songs, and began saying that his motto was “If you can’t write, rewrite. If you can’t rewrite, copyright.”

For a while there, every time he needed a few bucks, he would go to the library and thumb through some obscure folklore collection, then go up to Moe Asch at Folkways Records and say, “You know, Moe, I was just looking through your catalog, and I noticed that you don’t have a single album of Maine lumberjack ballads.”

All of which said, I was right as well: having a record out made an immediate difference in terms of getting jobs, and the fact that it appeared on the Folkways label gave me the equivalent of the Good Folksinging Seal of Approval.

(Incidentally, further research has confirmed that if you must have a disaster, have it happen in the Midwest. Whatever their cultural quirks, those folks can be really nice.)

In any case, what were the odds on getting popped the same way twice in one night? Lightning doesn’t strike etc., etc. Well, just ask any lightning rod about that old saw.

All of this was done to the tune of a strident crusade against “beatniks”—the word had only recently been minted by Herb Caen of the Chronicle, bless him—in the gutter press. Until that damned word came along, nobody noticed us, or if they did it was just “those kids.” We had all the freedom anonymity could bestow—a lovely state of affairs.

Frisco was a place where lefties could really feel at home. In those days, it was still a working-class town and, since the general strike of 1934 (which I heard a lot about), a union town to boot. The joint was fully outfitted with hot and cold running Reds of every imaginable persuasion.

To be working seven nights a week was incredible to me. In a sense it was the first real test of my career plans, of whether I truly wanted to be a professional, full-time musician. And the answer was yes, without question or reservation. It also provided a lot of incentive to develop my music, build up my repertoire, all that kind of thing.

It was an absolutely essential education, because you can practice playing guitar in your living room, and you can practice singing in your living room, but the only place you can practice performing is in front of an audience. Those old coffeehouses did not have to shut down early like the bars did, so they would stay open as long as there were paying customers, and you would wind up working four or five sets a night. I think that is one of the things that set the folksingers of my generation apart from the performers coming up today. There are some very good young musicians on the folk scene, but they will get to be fifty years old without having as much stage experience as I had by the time I was twenty-five.

By the time I came on the scene, though, he was long gone from the Village. For most of the 1950s he was either on the West Coast or wandering around Europe with a banjo player named Derroll Adams,

The next evening Bob Gibson, who was riding very high in those days, gave half of his stage time to an unknown young singer named Joan Baez. That was Joanie’s big break, and anyone who was there could tell that it was the beginning of something big for all of us.

On the other hand, there were the beatniks, who were much the same sort of self-conscious young bores who twenty years later were dying their hair green and putting safety pins in their cheeks. We despised them, and even more than that we despised all the tourists who were coming down to the Village because they had heard about them.

In 1959 the poets still had very much the upper hand. I sometimes say, and there is more than a little truth to it, that the only reason they had folksingers in those coffeehouses at all was to turn the house. The Gaslight seated only 110 customers, and on weekend nights, there would often be a line of people waiting to get in. To maximize profits, Mitchell needed a way to clear out the current crowd after they had finished their cup of over-priced coffee, since no one would have bought a second cup of that slop. This presented a logistical problem to which the folksingers were the solution: you would get up and sing three songs, and if at the end of those three songs anybody was still left in the room, you were fired.

Basically, it turned out that we could draw larger crowds and keep them coming back more regularly. This was not because folk music is inherently more interesting than poetry, but singing is inherently theatrical, and poetry is not. Even a very good poet is not necessarily any kind of a performer, since poetry is by its nature introspective—“In my craft or sullen art / Exercised in the still night,” as Dylan Thomas put it. A mediocre singer can still choose good material and make decent music, while a mediocre poet is just a bore.

As in LA, we worked hard for the money, because being a coffeehouse it did not have to shut down when the bars shut down, so after “last call” at 4:00 A.M., we would get our second straight rush and that would sometimes keep us working until 7:00, 8:00, 9:00 in the morning. I loved walking up 6th Avenue on my way home to bed, watching all the poor wage slaves schlepping off to work.

He also used to preach sometimes in a storefront church, and his sermons were really remarkable. He would set up a riff on his guitar, and then he would chant his sermon in counterpoint to the riff, and when he made a little change in what he was saying, he would make a little change on the guitar. There was this constant interplay and interweaving of voice and guitar, and these fantastic polyrhythms would come out of that—I have never heard anything quite like it, before or since.

We used to hang around for hours, and we would talk and I would ask him how to play one thing or another. He used to say, “Well, playing guitar ain’t nothing but a bag of tricks”—which I suppose is true in a way, but he had a very, very big bag.

You can listen to the records I did for Folkways, and then my first recordings for Prestige, and you will hear a huge difference in the guitar playing, and Gary is largely responsible for that change.

Being blind, he was a target for people who would grab his guitar and run off, so as a result he never let it out of his hands. He used to take it with him into the bathroom—and he would play there. He also had concluded that he needed to be able to defend himself, so he used to carry this big .38 that he called “Miss Ready.” He would pull out this gun and show it to me, and one time, as diffidently as I could, I said, “You know, Gary, you are blind. Don’t you think maybe it’s not such a good idea . . .” He said, “If I can hear it, I can shoot it.”

he turned those books over to the press. That made a lot of noise, and at one point some lieutenant came down and informed John that if he kept stirring up trouble, he was going to be shot while resisting arrest.

And there was this weird rule that no applause was permitted, because all these old Italians lived on the upper floors and they would be bothered by the noise and retaliate by hurling stuff down the airshaft. So instead of clapping, if people liked a performance they were supposed to snap their fingers. Of course, along with solving the noise problem, that also had some beatnik cachet.

For a couple of years after that, the streets were pretty cool, but around 1961–62 it got nasty again, this time with the focus on blacks and especially interracial couples. In a way, the real issue was neither homosexuality nor race; it was that this had been the old residents’ turf and they were losing it. The rents were going up and the locals were feeling threatened, so the kids were taking it out on the most obvious outsiders.

Basically, what I think happened was that the New York singers simply were not as competitive as the newcomers. You do not stick it out in this line of work unless you are fiercely driven, and most of the New Yorkers, while they might have had the talent, did not have that competitive drive. It was simple economic determinism: they were going to college, getting money from their parents, and however much they might have told themselves that their real focus was the music, when push came to shove, they found they had an easier time doing whatever they were learning to do in school.

Even the people who got to be very, very good were not necessarily that way when they arrived. Phil Ochs was not a better performer than Roy Berkeley when he started working in the Village; he just needed it more. I was one of the few New Yorkers to stick it out, and that was because I was stuck with it.

During Milos’s tenure I started running the Tuesday night hootenannies (what would now be called “open mikes”), which I continued through the early 1960s.

That man had more capacity for enjoyment than anyone I have ever known; he could have found something amusing about Hell.

After the set, Fred introduced us. Bob Dylan, spelled D-Y-L-A-N. “As in Thomas?” I asked, innocently. Right. I may have rolled my eyes heavenward. On the other hand, all of us were reinventing ourselves to some extent, and if this guy wanted to carry it a step or two further, who were we to quibble? I made my first acquaintance with his famous dead-fish handshake, and we all trooped back to the Kettle for another drink. The Coffeehouse Mafia had a new recruit.**

The first thing you noticed about Bobby in those days was that he was full of nervous energy. We played quite a bit of chess, and his knees would always be bouncing against the table so much that it was like being at a séance. He was herky-jerky, jiggling, sitting on the edge of his chair. And you never could pin him down on anything. He had a lot of stories about who he was and where he came from, and he never seemed to be able to keep them straight.

What he said at the time, and what I believe, is that he came because he had to meet Woody. Woody was already in very bad shape with Huntington’s chorea, and Bobby went out to the hospital and, by dint of some jiving and tap dancing, managed to get himself into his presence, and he sang for Woody, and he really did manage to develop a rapport with him. For a while, he was going out to the hospital quite often, and he would take his guitar and sit there and play for Woody.

We all admired Woody and considered him a legend, but none of us was trucking out to see him and play for him. In that regard, Dylan was as stand-up a cat as I have ever known, and it was a very decent and impressive beginning for anybody’s career.

Bobby was doing guest sets wherever he could and backing people up on harmonica and suchlike, but there was no real work for him. He was cadging meals and sleeping on couches, pretty frequently mine.

and Peter Stampfel, who became the guiding light of the Holy Modal Rounders and later one of the Fugs. We didn’t socialize as much with them, except for Peter, who has always been one of my favorite people and is undoubtedly some kind of genius—though so far, no one has ever figured out what kind.

Back then, he always seemed to be winging it, free-associating, and he was one of the funniest people I have ever seen onstage—although offstage no one ever thought of him as a great wit.

And his repertoire changed all the time; he’d find something he loved and sing it to death and drop it and go on to something else. Basically, he was in search of his own musical style, and it was developing very rapidly. So there was a freshness about him that was very exciting, very effective, and he acquired some very devoted fans among the other musicians before he had written his first song, or at least before we were aware that he was writing.

Now, Jack’s mother and father were very prominent people in Brooklyn; I understand that his father was chief of surgery in a hospital, and the family had been in medicine for several generations. So the fact that Jack had turned into a bum was a great source of grief. However, he had been away for a long time, and now he was home, and they were making some attempt at a reconciliation, so Dr. and Mrs. Adnopoz came down to see the kid. I was sitting at a front table with them and the cowboy artist Harry Jackson, and Jack was onstage, and he was having some trouble tuning his guitar. The audience was utterly hushed—a very rare occurrence in that room—and Mrs. Adnopoz was staring at Jack raptly, and then she lets out with a stage whisper: “Look at those fingers . . . Such a surgeon he could have been!”

But there was a sort of Village cabal that had a certain amount of influence within our small world, and among other things, we pushed Mike Porco to book Bobby. Terri had been helping Mike by doing this, that, and the other thing, but she really had to call in every favor to get Bobby that gig. In the end, Mike put him on opening for John Lee Hooker, and it went OK. Then a few months later he opened for the Greenbriar Boys, and Bob Shelton wrote him up in the Times, and that was really what got Bobby started.

Still, there was a definite groundswell of interest, and he soon had a small but fanatical claque of fans who would show up anywhere he was playing; if he dropped by to do a guest set at the Gaslight or one of the other clubs, they would appear by the second song.

Baez was a completely different kind of artist. With her, it was all about the beauty of her voice. That voice really was astonishing—the first time I heard her she electrified me, just as she electrified everybody else. She was not a great performer, and she was not a great singer, but God she had an instrument. And she had that vibrato, which added a remarkable amount of tone color. I think that I was a technically better singer than she was even then, but she had a couple of tricks that were damn useful, and I learned a few things from her.

The thing about Baez, though, was that like almost all the women on that scene, she was still singing in the style of the generation before us. It was a cultural lag: the boys had discovered Dock Boggs and Mississippi John Hurt, and the girls were still listening to Cynthia and Susan Reed. It was not just Joan. There was Carolyn Hester, Judy Collins, and people like Molly Scott and Ellen Adler, who for a while were also contenders. All of them were essentially singing bel canto—bad bel canto, by classical standards, but still bel canto. So whereas the boys were intentionally roughing up their voices, the girls were trying to sound prettier and prettier and more and more virginal.

When Dylan met Grossman, it was truly a match made in heaven, because those were two extraordinarily secretive people who loved to mystify and conspire and who played their cards extremely close to their vests. You never knew what scheme Albert was cooking up behind that blank stare, and he actually took a sort of perverse pleasure in being utterly unscrupulous.

It also introduced the piece that some people continue to regard as my signature song, “Cocaine Blues.”

In a lot of ways the difference was economic. By that time, the scene in New York was relatively professional, made up of all these people who were coming into town and needed to make a living from their music just to pay the rent. We were playing five sets a night in rooms full of drunken tourists, and even if we didn’t necessarily think of ourselves that way, we were professional entertainers. Cambridge was a college town, and the scene—not necessarily the performers but the fans and the hangers-on—was a bunch of middle- and upper-middle-class kids cutting a dash on papa’s cash.

People started asking me to do “that Dylan song—the one about New Orleans.” This became more frequent as Bobby’s popularity took off, and with a combination of annoyance and chagrin, I decided to drop the song until the whole thing blew over. Then, sometime in 1964, Eric Burdon and the Animals made a number-one chart hit out of the damn thing. Same arrangement. I would have loved to sue for royalties, but I found that it is impossible to defend the copyright on an arrangement. Wormwood and gall. I also heard that Bobby had dropped the tune from his repertoire because he was sick of being asked to do “that Animals song—the one about New Orleans.”

There is one final footnote to that story. Like everybody else, I had always assumed that the “house” was a brothel. But a while ago I was in New Orleans to do the Jazz and Heritage Festival, and my wife Andrea and I were having a few drinks with Odetta in a gin mill in the Vieux Carré, when up comes a guy with a sheaf of old photographs—shots of the city from the turn of the century. There, along with the French Market, Lulu White’s Mahogany Hall, the Custom House, and suchlike, was a picture of a forbidding stone doorway with a carving on the lintel of a stylized rising sun. Intrigued, I asked him, “What’s that building?” It was the Orleans Parish women’s prison.

What had happened, as it turned out, was that Jack Elliott, who had been on before us, had finished his set by throwing his hat in the air, and he chose that moment to come out and retrieve it. He was goofing around behind us, waving at the crowd, and I had no idea what was going on, and was simply dying. I later learned that as Jack walked off, Terri met him at the side of the stage and coldcocked him, knocked him flat on his ass. Small consolation.

One of the odd things about him was that he did not like beds; he preferred a good, comfortable armchair. He was the easiest man to put up overnight: “Here John, we have a couch.” “Oh, I don’t need a couch. Say, that looks like a great chair

He started watching my right hand, and he said, “You’ve got those basses backward.” And he played me a few measures of it the way he did it. It was just like on the record, and by God, he was right. I said, “Oh, shit, back to the old drawing board.” And he says, “No, no, no. You really ought to keep it that way. I like that.” That’s the folk process for you: some people call it creativity, but them as knows calls it mistakes.

By now that man has been dead for almost forty years, and he’s probably still in better shape than I am.

There will undoubtedly be times when there is a heightened interest in folk music, but we simply do not have the deep sources of talent that we had in the 1960s. Unless we can hatch another generation like Gary, Skip, and John, or John Lee and Muddy Waters, the quality will be sadly second-rate—and the world that produced those people is long gone.

That was one of the most important things about their music, and why they had become famous in the first place: because they played and sang like people who knew who they were. So they were not people who could be overawed all that easily. It doesn’t much matter if you are a sharecropper from Texas or a Harvard grad; if you don’t know who you are, you are lost wherever the hell you find yourself, and if you do, you do not have much of a problem.

As for Joni Mitchell or Leonard Cohen, they have as much to do with folk music as Schubert or Baudelaire.

In an attempt to avoid the migraines brought on by serious thought, most of the critics and music marketers have relied on a simple formula: if the accompaniment to this music is acoustic, it’s folk music. With amplified backup, it’s rock ’n’ roll, except in those instances where a pedal steel guitar is added, in which case it’s country. To be fair to the critics—which is no fun at all—the performers themselves have rarely been more perceptive when it comes to labeling their work.

“OK, if I’m gonna be a songwriter, I’d better be serious about it.” So he set himself a training regimen of deliberately writing one song every day, and he kept that up for about a year. The songs could be good, bad, or indifferent; the important thing was that it forced him to get into the discipline of sitting down and writing.

think people like Joni Mitchell and Leonard Cohen felt toward Dylan sort of the way Ezra Pound felt toward Walt Whitman: “You cut the wood; now it’s time for carving.”

I was working down at the Gaslight, and I opened my set with “This Land Is Your Land” and closed it with “The International,” including the verse that goes, “We want no condescending saviors.”

The core problem with the New Left was that it wasn’t an ideology, it was a mood—and if you are susceptible to one mood, you are susceptible to another.

Phil’s chord sense was quite advanced, and he was the only person around aside from Gibson who used the relative minor and secondary keys. He was also one of the few songwriters on that scene who knew how to write a bridge.

As a lyricist, there was nobody like Phil before and there has not been anybody since. That is not to say that I liked everything he wrote, but he had a touch that was so distinctive that it just could not be anybody else.

Like a lot of people on that scene, Phil was essentially a Jeffersonian democrat who had been pushed to the left by what was happening around him. Two consecutive Democratic presidents had turned out to be such disappointments that it forced a lot of liberals into a sort of artificial left-wing stance, and Phil was of that stripe. That may seem a surprising thing to say about the man who wrote “Love Me, I’m a Liberal,” but I think it is accurate. He had believed in the liberal tradition, and it had betrayed him, and naturally he had a special contempt for the people who espoused lukewarm liberal views but were supporting the Cold War, the war in Vietnam, the crackdown on the student movement.

Dylan was never as devoted to politics as Phil was, but I think that if you could have managed to pin him down, his views were roughly similar. He was a populist and was very tuned in to what was going on—and, much more than most of the Village crowd, he was tuned in not just to what was going on around the campuses but also to what was going on around the roadhouses. But it was a case of sharing the same mood, not of having an organized political point of view. Bobby was very sensitive to mood, and he probably expressed that better than anyone else. Certainly, that was Phil’s opinion. Phil felt that Bobby was the true zeitgeist, the voice of their generation.

One of the great myths of that period is that Bobby was only using the political songs as a stepping stone, a way to attract attention before moving on to other things. I have often heard that charge leveled against him, and at times he has foolishly encouraged it. The fact is, no one—and certainly not Bobby—would have been stupid enough to try to use political music as a stepping stone, because it was a stepping stone to oblivion. Bobby’s model was Woody Guthrie, and Woody had written a lot of political songs but also songs about all sorts of other subjects, and Bobby was doing the same thing.

In a way, the whole question of who influenced whom is bullshit. Theft is the first law of art, and like any group of intelligent musicians, we all lived with our hands in each other’s pockets. Bobby picked up material from a lot of people, myself included, but we all picked up things from him as well.

Within a couple of years, Bobby changed the whole direction of the folk movement. The big breakthrough was when he wrote “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall,” because in that song he fused folk music with modernist poetry. The tune was borrowed from an old English ballad called “Lord Randall,” and it was in the same question-and-response form, but the imagery was right out of the symbolist school.

Somewhere in my bookcases I probably still have a paperback collection of modern French poetry with Bobby’s underlinings in it. I have never traced any of the underlinings to anything he actually used in a song, but he was reading that stuff very carefully.

Blues is like a kielbasa, those long Polish sausages: you don’t sing a whole blues, you just cut off a section.

am absolutely ruthless about this, because I have no incentive to pad my repertoire with second-rate material of my own when I could just as easily add some first-rate material by someone else.

Poetry is automatically suspect to me, because if you are a good enough poet, you can make bullshit sound so beautiful that people don’t notice that it’s bullshit. I used to hear Dylan Thomas over at the old White Horse Tavern back in the 1950s, and when he had had enough to drink—which was frequently—he would recite his poetry, and my jaw would drop. It was beautiful, gorgeous stuff, and he recited it marvelously. But when I would go back and look at it on the page, a lot of it was bullshit. Not all of it, by any means, but I would challenge anyone to explain what some of those things were about.

I think it was a good thing that, back in the Renaissance, people like Michelangelo were treated like interior decorators. A well-written song is a craft item. Take care of the craft, and the art will take care of itself.

Leonard Cohen used to point out that the greatest problem for a writer is that your critical faculties develop faster than your creative faculties, and it is very easy to get so wrapped up in what is wrong with your songs that you quit writing entirely.

- Personally, I did not have to worry about this. I showed my draft card to a guy I knew over at the War Resisters League, to find out what my classification meant in terms of getting hauled off by the Feds, and he glanced at it and drawled: “Well, what it means is that when the Red Army is marching down 5th Avenue, you’ll be told, ‘Don’t call us, we’ll call you.’”

Most of the songwriters were writing well below their abilities, and people who were capable of learning and employing more complicated harmonies and chord structures confined themselves to 1-4-5 changes. Some of them were enormously talented, but they were like an enormously talented boxer who insists on fighting with one hand behind his back. The result was that we produced a Bob Dylan, a Tom Paxton, a Phil Ochs, a bit later a Joni Mitchell—but we did not produce a Johann Sebastian Bach or a Duke Ellington.

For me, one of the great things about that period was that I could make a living without leaving the Village. I was working weeks and weeks on end in clubs that I could walk to, so my living room was my dressing room, and I could even go home between sets. I was listening to music that interested me, and making music that interested my friends, and I felt that I belonged to a community of singers, songwriters, performers who were really cooking.

And I knew perfectly well that none of us was a true “folk” artist. We were professional performers, and while we liked a lot of folk music, we all liked a lot of other things as well. Working musicians are very rarely purists. The purists are out in the audience kibitzing, not onstage trying to make a living. And Bobby was absolutely right to ignore them.

The other reaction, which was even more damaging, was “I’m gonna be next. All I have to do is find the right agent, the right record company, the right connections, and I can be another Bob Dylan!” Yeah, sure you could. All you had to do was write “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall”—for the first time. That was what Bobby had done, and none of the rest of us did that. Bobby is not the greatest songwriter in history, but he was far and away the best on our scene, and whether we admitted it or not, we all knew that.

so when the scene shut down, I felt the satisfaction of a Seventh Day Adventist on the day the world really does come to an end.

liked the Village, and I still like it, and I would not like to live anywhere else. The country is a city for birds.

Dave was the most voracious reader I have known, and he would send me home with thick volumes of history or slim paperbacks of his favorite science fiction—“It’s mind rot, but good mind rot,” he would say.

I was with him when Sunday Street came out, the first solo album he had done in years.

“but if I start bloviating about how wonderful it was, what I say and what you hear will not be the same thing. It has been my observation that when you ask some alter kocker about the old days, his answer—however he may phrase it—will always be, ‘Of course, everything was much better then, because I could take a flight of stairs three at a time.’