Music

-

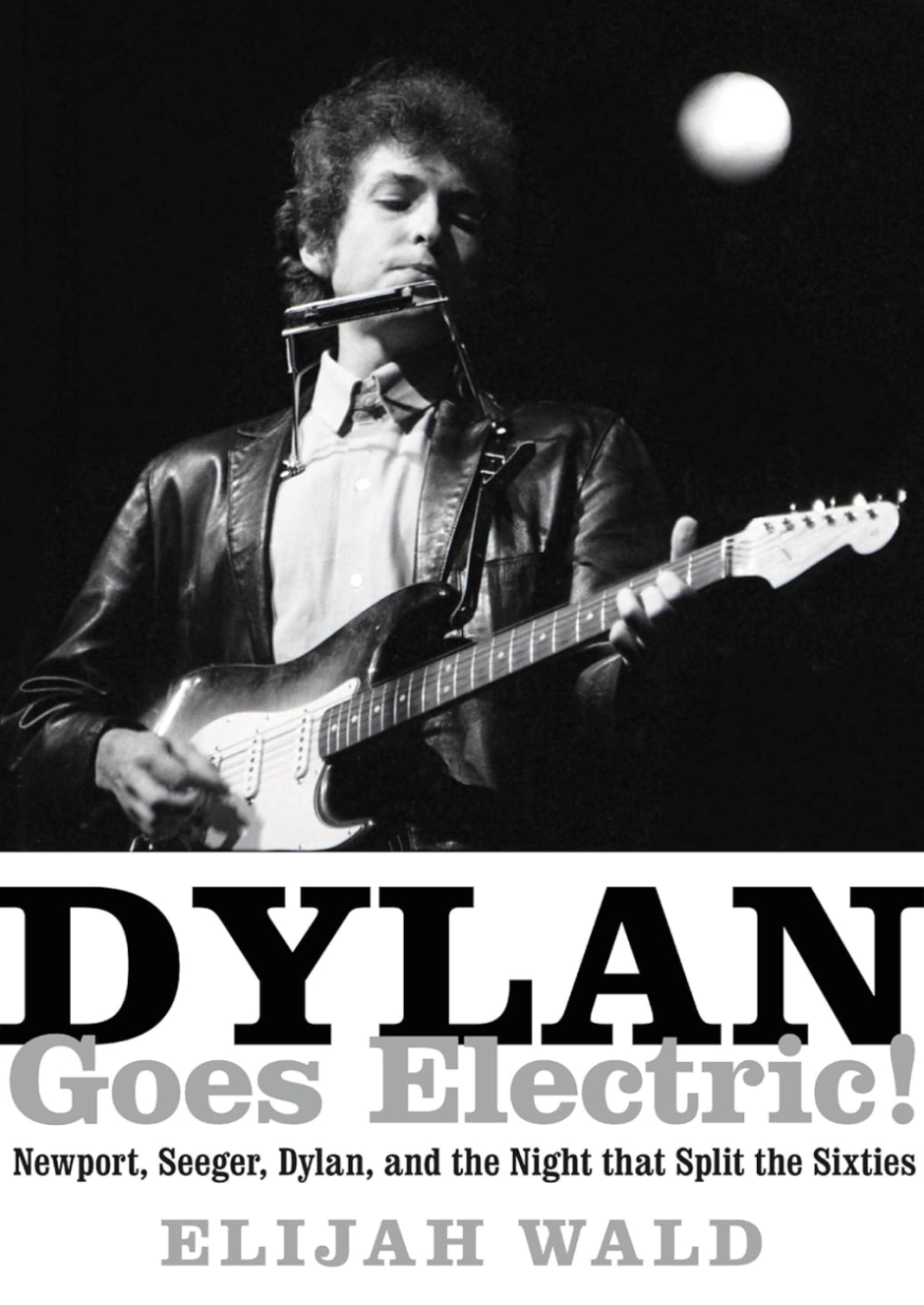

Dylan Goes Electric by Elijah Wald

The book in 3 sentences

An excellent history of the Greenwich Village folk scene in the late 1950s and early 1960s, American folk music in general and early Dylan in particular. It filled in a lot of gaps in my understanding of the music, the people and the time period. How so much musical genius could coalesce and enhance each other is a marvel to behold. It’s easy to forget how hard music was to come by in that time. These days you can just say something into the air and a song will start to play, but in the 1950s if you wanted to hear Appalachian ballads you had to actually go to Appalachia, listen to radio stations you probably could not get, or luck into a friend with an improbably rare record collection.

Greenwich Village being a nexus of folk music talent meant that the folk singers from all over America could just come and swap songs – basically switching from intellectual and musical high latency and low bandwidth musical environment to a low latency and high bandwidth musical environment.

There was also a buildup of talent in Greenwich Village, and then for whatever (not really that related) reason tastes and styles went in the folk music direction and there was a wealth of talent to choose from. The amount of folk music in the highest selling records of the time period surprised me quite a bit.

How I Discovered It

I watched the movie “A Complete Unknown”

Who Should Read It?

Anyone interested in the music or the time period.

How the Book Changed Me

- The primary changes were the ones mentioned above, the main one not mentioned so far is the role of Pete Seeger. I started the book thinking that the movie exaggerated his importance and probably combined several people into one character, but after reading the book, if anything the movie minimized his role in American folk music. He did a staggering amount of work for a staggering number of years just keeping folk music as folk music a going concern. Before it appears in the comments (ha!) yes – the Stalin’s Songbird title is appropriate but meaningless. Folk singer political opinions do not count.

Highlights

Seeger was a hard man to know and sometimes a hard man to like, but he was an easy man to admire, and he backed up his words and beliefs with his actions. Some people might think it was hokey to build that house with his own hands, the Harvard boy homesteading on a patch of prairie an hour and a half north of Manhattan.

In retrospect that legend often overshadowed his work, and it is easy to forget what the work was. This is particularly true because Seeger was first and foremost a live performer, and only a shadow of his art survives on recordings. That was fine with him—he always felt the recordings were just another way of getting songs and music out into the world. If you complimented him, he would suggest you listen to the people who inspired him, and a lot of us did and discovered Woody Guthrie, Lead Belly, Uncle Dave Macon, Bob Dylan, and hundreds of other artists whose music we often liked more than his.

Pete would quote his father, Charles Seeger: “The truth is a rabbit in a bramble patch. One can rarely put one’s hand upon it. One can only circle around and point, saying, ‘It’s somewhere in there.’”

There were myriad views and conceptions of the folk revival, but in general they can be divided into four basic strains: the encouragement of community music-making (amateurs picking up guitars and banjos and singing together with their friends); the preservation of songs and styles associated with particular regional or ethnic communities (the music of rural Appalachia, the Mississippi Delta, the western plains, the Louisiana Cajun country, the British Isles, Congo, or anywhere else with a vibrant vernacular culture); the celebration of “people’s music” and “folk culture” as an expression of a broader concept of the people or folk (linking peasant and proletarian musical traditions with progressive and populist political movements); and the growth of a professional performance scene in which a broad variety of artists were marketed as folksingers. People committed to one of those strains often tried to distance themselves from people identified with another—purists criticized popularizers, popularizers mocked purists—but they all overlapped and intertwined, and all flowed directly from Pete Seeger.

Seeger’s name was inherited from a German great-great-grandfather who immigrated to the United States in 1787, but most of his ancestors had come over from England in the early Colonial period. His parents were classical musicians, his mother a violinist and his father a pianist and musicologist. A photo from 1921 shows two-year-old Pete seated on his father’s lap as his parents play music in a dirt clearing between their homemade wooden trailer and a makeshift tent. They were trying to bring culture to the common people, touring in support of socialism and the populist dissemination of “good” music.

He was briefly home from one of a series of boarding schools, which led to Harvard, which he dropped out of at nineteen, moving to New York City to be a newspaper reporter.

He was acting on Woody’s exhortation to “vaccinate yourself right into the big streams and blood of the people,” and recalled that trip as an essential part of his education, later advising young fans to spend their summer vacations hitchhiking around the country, meeting ordinary folks and learning how to fend for themselves in unfamiliar territory.

That would always be Pete’s unique talent: no matter the audience, no matter the situation, he could get people singing.

explaining that in country cabins the only books you’d find were a Bible and an almanac, one to get you to the next world and the other to see you through this one.

Seeger had always been shy, and the philosophy of anonymous participation suited his nature as well as his political beliefs—though it caused some friction in the Almanac Singers, since he and most of the others felt their songs should be presented as anonymous, communal creations, while Guthrie wanted to be properly credited for his work.

Though often attacked as a “Communist front,” People’s Songs received little encouragement from the Party, which did not think folk songs were likely to appeal to urban proletarians and preferred to cultivate artists like Duke Ellington—Seeger recalled a Communist functionary telling him, “If you are going to work with the workers of New York City, you should be in the jazz field. Maybe you should play a clarinet.”

Mostly, though, he worked on the Bulletin, presented educational programs about folk music, and played at benefits, square dances, and community events like the Saturday morning “wing-dings” he held for kids in his Greenwich Village apartment.

He and Toshi were living in the basement of her parents’ house on MacDougal Street—her Japanese father and Virginian mother were committed radicals, so he fit right in—and Pete seems to have been happy with this situation, earning minimal pay, serving progressive causes, and, in his words, “congratulating myself on not going commercial.”

“On Top of Old Smoky” (on which Pete created a model for future sing-along leaders by speaking each line before the group sang, like a preacher “lining out” a hymn),

The Trio added a new, young, collegiate flavor and became the defining pop-folk group of the early 1960s. In 1961 the Highwaymen followed with “Michael, Row the Boat Ashore,” and the Tokens topped the charts by adding jungle drums and new lyrics to “Wimoweh” and retitling it “The Lion Sleeps Tonight.” The next year the Trio reached the Top 40 with Seeger’s “Where Have All the Flowers Gone”; Peter, Paul, and Mary got their first Top 10 hit with his “Hammer Song” (retitled “If I Had a Hammer”); and by 1965 the Byrds were at number one with his “Turn, Turn, Turn.”

Alan Lomax grumbled, “Peter looked at folk music as something to bring everybody in, whether they could sing or play in tune or anything like that.” Lomax, by contrast, wanted to focus attention on authentic proletarian artists and music. He was happy when a well-known entertainer was willing to help with that mission, whether it was the Weavers or a pop-jazz singer like Jo Stafford, but was annoyed that Pete encouraged urban amateurs to think they were carrying on folk traditions.

Pankake’s article underscored an essential fact: as the folk scene grew through the 1950s, it split into cliques that often bickered bitterly, but all came through Seeger, and while his recordings with the Weavers parented the pop-folk style, he was simultaneously parenting its traditionalist opponents.

As a result, although he was by far the most prolific recording artist on the folk scene, issuing six albums a year from 1954 through 1958, his playing and singing were often more workmanlike than thrilling, and it is easy to underestimate both his skills and his influence on other players.

To Seeger, everything was political. His belief in folk music fitted with his beliefs in democracy and communism, and if he was often troubled by the fruits of those beliefs, he remained undaunted, repeating, “All you can do in this world is try.” During the 1950s he did not record many explicitly political songs, in part due to Cold War paranoia but also because his years with the Almanac Singers and People’s Songs had made him aware of the limitations of that approach. He had hoped to support a singing labor movement, but found that “most union leaders could not see any connection between music and pork chops” and ruefully noted that by the late 1940s, “‘Which Side Are You On?’ was known in Greenwich Village but not in a single miner’s union local.” In the formulation of his biographer David Dunaway, he concluded that the most effective way to connect his music to his politics was by singing songs by the working class rather than writing songs for it.

But it was not the kind of music Pete wanted to be playing, and when the Weavers were hired to do a cigarette commercial a month and a half later, it was the final straw. As the group’s sole nonsmoker, he bowed to the democratic process and did the session, but quit immediately afterward, noting “the job was pure prostitution . . . [and] prostitution may be all right for professionals—but it’s a risky business for amateurs.”

By March 27, 1961, when Seeger’s case finally went to trial, the Kingston Trio’s “Tom Dooley” had kicked off a full-scale folk boom and the week’s top five albums included discs by the Trio, the Brothers Four, and the Limeliters. Folk ensembles accounted for ten of the thirteen best-selling albums by duos or groups, the Seegerless Weavers among them. Smoothly polished trios and quartets were still by far the most popular folk acts; although Joan Baez had released her first album in January and Billboard tipped it as a disc to watch, it was still just reaching the cognoscenti.

“Some jail will be a more joyous place if he lands there, and things will be bleaker on the outside.”

Seeger came of age in the Depression and never lost the sense that economic inequality was the root of humanity’s problems, that a vast majority of working people was threatened and subjugated by a tiny minority of rapacious capitalists, and that the only solution was to organize mass movements that would harness the people’s numbers to combat the oppressors’ wealth. Twenty years later, Dylan grew up in the most economically equitable era in American history. World War II had jump-started the US economy, and New Deal reforms meant that wealth was spread more evenly than ever before. When he wanted a car or a motorcycle, his father bought one for him, and a lot of his friends had cars or motorcycles too.

The battles of his youth were not organized political struggles; they were individual gestures of protest against the placid conformity of his elders and his less imaginative peers.

For a teenager bursting with unfocused energy, the country and western style was too restrained and also too widely available. He needed music that not only captured his imagination but set him apart, and found it in the R & B broadcasts he picked up on his bedside radio after the staid local programming had gone off the air. KTHS,

In the 1930s and 1940s radio had been dominated by national networks that beamed The Kraft Music Hall, Your Hit Parade, Amos ’n’ Andy, and The Lone Ranger into every home with electricity, but in the 1950s that role was taken over by television, and radio became a haven for local programming, ethnic programming, niche markets, and small sponsors.

In the 1930s Seeger had to travel to the Asheville Folk Festival to find the raw southern sounds that changed his life, but Dylan made the same journey without leaving his bedroom. To some extent that meant they had different relationships to the music: for Seeger it was inextricable from the communities that created it and the historical processes that shaped those communities, while for Dylan it was a private world of the imagination.

“Trying to make life special in Hibbing was a challenge. . . . Rock ’n’ roll made Bob and me feel special because we knew about something nobody else in Hibbing knew about. . . . We started losing interest in Elvis after he started becoming popular.”

In the right circles, obscure musical knowledge was social currency.

Kegan was a city boy whose regular singing partners included several African American teenagers, and they may have been the first black people Dylan met.

One way or another, he kept performing through his high school years.

Bob’s main instrument in this period seems to have been piano,

Aside from music, his other passion was movies—his uncle owned the local theater, so he could go as often as he wanted—and friends recalled him being particularly fascinated by Rebel Without a Cause, watching it over and over and buying a red jacket like James Dean’s character wore.

Not only was Dandy playing the right kind of records, when Bob and Bucklen inquired about him it turned out that he was African American—in Bucklen’s estimate “the only black guy within fifty miles.” That alone would have been enough to fascinate Bob.

Like many grown-ups in the R & B business, he regarded what he played on the radio as a compromise with the crude tastes of a mass public and preferred the intricate explorations of cool jazz and hard bop: Bucklen remembers him saying, “I like blues. I like rock music. But there’s no depth to it like jazz.”

an uncle—gave him an album of Lead Belly 78s. The next day he called Bucklen: “Bob almost shouted over the phone: ‘I’ve discovered something great! You got to come over here!’”

A teenager who disdained Elvis Presley as a pale imitation of Clyde McPhatter and got excited about Lead Belly was not going to have his world changed by the Kingston Trio.

Belafonte had originally modeled himself on Josh White, the black guitarist and singer from South Carolina who made rural blues palatable to New York cabaret audiences, then branched out into left-wing topical songs and Anglo-American ballads.

For a young musician who had trouble keeping bands together, there was an obvious appeal to music that could be played solo,

Odetta’s rich blend of bel canto and blues provided a connection to the artists Dylan already loved. If his voice sounded nothing like hers, that was hardly a barrier for someone who had previously modeled himself on Little Richard, and he arrived in Minneapolis with a repertoire largely drawn from her records: “Santy Anno,” “Muleskinner Blues,” “Jack o’ Diamonds,” “’Buked and Scorned,” “Payday at Coal Creek,” “Water Boy,” “Saro Jane,” and his first Woody Guthrie songs, “Pastures of Plenty” and “This Land Is Your Land”—the two Odetta had recorded.

judging by what survives on early tapes his second-strongest influence was yet another classically trained black folksinger, Leon Bibb,

Dylan was also thinking more professionally than most people on the scene.

He was naturally shy, but performing brought something out in him: “I could never sit in a room and just play all by myself,” he wrote. “I needed to play for people and all the time.” It was a way of relating to his new acquaintances, but also in some respects a way of shutting them out, and not everyone was supportive. “You’d go to a party and Bob would get a chair and move right into the center of the room and start singing,” Weber recalled. “If you didn’t want to listen, you got the hell out of the room, and I resented it.”

He stopped going to classes in his first semester and instead hung out in coffeehouses, bars, and friends’ apartments, soaking up conversation, music, books, and the Bohemian culture that had been so lacking in Hibbing.

They had mistaken commercial pap for authentic folk art, and it was their duty to rescue other innocents who had been similarly beguiled.

But Dylan was enthralled and inspired: when Pankake went out of town for a couple of weeks he helped himself to a bundle of records, and his current girlfriend, Bonnie Beecher, recalled him playing the Elliott albums, one after another, insisting that she recognize their brilliance: “Literally, you are in this room until you’ve heard them all, and you get it.”

Guthrie exerted a strong influence on both men, but they were also linked in other ways—both Jewish, middle-class, introverted loners who reinvented themselves as mythic wandering minstrels. Woody was an inspiration as much for his anarchic independence as for his specific musical skills, and although they sang dozens of Guthrie’s songs, that was almost an afterthought.

The Guthrie of Bound for Glory is a drifting hobo folksinger, picking up songs wherever he goes, sometimes improvising a lyric to suit a particular situation, but in general singing the familiar songs of ordinary working people. The real Guthrie spent a lot of time at a typewriter but sang a similar range of material, and on records, radio, and stage performances he showed no preference for his own compositions. For Dylan, Guthrie was exciting as a singer, player, and songwriter, but most of all as a man who lived life on his own terms. Given how large Guthrie has loomed in Dylan’s biographies, one of the most striking things about the surviving tapes of that year and a half in Minneapolis is how little Guthrie material is on them: a scant five songs, at least four of which Dylan had learned from other people’s recordings.

Nelson remembered Dylan changing instantly and dramatically after hearing those first Jack Elliott albums: “He came back in a day, or two at the most, and . . . from being a crooner basically, nothing special . . . he came back and sounded like he did on the first Columbia record.”

Little Richard and Odetta had been inspirational models, but Guthrie was more than just an exciting musician: he was a storyteller, a legend, and that fall he seems to have become a fixation.

a bunch of Woody’s letters from the hospital in New Jersey where he had been confined since the mid-1950s

Bob Dylan arrived in New York in January 1961 and headed to Greenwich Village, where he introduced himself to the local scene by playing a couple of songs at a coffeehouse on MacDougal Street.

in any case within that first week he met Guthrie, sang for him, and established himself as one of the few young performers who had a direct connection to Woody, not only as a legend but as a person.

More than that, he established himself with the New York folk crowd as a new incarnation of the Woody who had rambled out of the West twenty years earlier.

“There were detractors who accused Bob of being a Woody Guthrie imitator,” says Tom Paxton, a singer from Oklahoma who had arrived in the Village a year or so earlier. “But that was silly on the face of it, because Jack Elliott was a more conscious Woody clone than Bob ever was. When Bob sang Woody Guthrie songs it was very distinctive, but Bob sang like Bob right from the beginning.” Seeger agreed: “He didn’t mold himself upon Woody Guthrie. He was influenced by him. But he was influenced by a lot of people. He was his own man, always.”

Dylan loved Guthrie’s songs and cared about visiting him and singing for him, and some people close to Woody felt that Dylan established a stronger connection than any of the other young singers who made the pilgrimage.

Anyone hoping to understand the cultural upheavals of the 1960s has to recognize the speed with which antiestablishment, avant-garde, and grass-roots movements were coopted, cloned, and packaged into saleable products and how unexpected, confusing, and threatening that was for people who were sincerely trying to find new ways to understand the world or to make it a better place.

In terms of folk music in the early 1960s, it seemed pretty clear what kind of far-out was selling. “Rockless, roll-less and rich, the Kingston Trio by themselves now bring in 12% of Capitol’s annual sales, have surpassed Capitol’s onetime Top Pop Banana Frank Sinatra,”

In 1961 the Trio was the best-selling group in the United States, accounting for seven of Billboard magazine’s hundred top LPs. Harry Belafonte had three, the Limeliters had one,

Normal people might find it amusing to visit the Café Bizarre or the Wha? and see the weirdos in their native habitat, but the Kingston Trio was not only more polished and entertaining; they were also more honest: as Dave Guard said, “Why should we try to imitate Leadbelly’s inflections when we have so little in common with his background and experience?” The Bohemians were a bunch of poseurs who dressed badly, listened to screechy music, and were at best ridiculous and often frankly annoying. Of course, the Bohemians saw the situation rather differently: to them, the Trio and its fans were a bunch of empty-headed conformists marching in lockstep to the drumbeat of Madison Avenue and the Cold War military-industrial complex, and any effort to succeed on the commercial folk scene represented a compromise with a corporate culture that was bland, retrograde, and evil—the culture of blacklisting, segregation, and nuclear annihilation.

In 1963, Dylan’s girlfriend Suze Rotolo was told that her cousin’s husband, a career army officer, had lost a promotion that required security clearance because she was pictured with Dylan on the cover of his Freewheelin’ album,

Through most of the 1950s serious fans drew a distinction between authentic folksingers, who played the traditional music of their communities, and “singers of folk songs” like Seeger, Burl Ives, Richard Dyer-Bennett, and Odetta, who performed material collected in those communities but had not grown up in the culture.

Van Ronk, a leading figure in this group, later dubbed them the “neo-ethnics.” Some played old-time hillbilly music, some played blues, some sang medieval ballads, and there were lots of other flavors in the mix:

Music was permitted in the park from noon till five, and if you weren’t sated by then there would be a hootenanny and concert that evening at the American Youth Hostels building on Eighth Street. Then serious pickers and singers would convene at 190 Spring Street, where several musicians had apartments, or in various other lofts, basements, and walk-ups around the Village or Bowery, and the playing would continue till dawn. In terms of hearing new songs and styles, meeting other musicians, and building skills and repertoire, the parties were at least as important as the clubs and coffeehouses. The Village musicians all learned from one another and were each other’s most important audience.

They reshaped songs and arrangements to fit their tastes and talents, but always within the musical languages of the rural South, and within three years had recorded six albums for Folkways and spawned imitators across the country.

But music was always at the heart of it, and soon Dylan was playing decent fingerstyle guitar and singing a lot more blues.

Eric Von Schmidt was a painter, guitarist, and the uproarious Bohemian godfather of the Harvard Square scene, combining Van Ronk’s devotion to old jazz and blues with Elliott’s anarchic enthusiasm.

“You heard records where you could, but mostly you heard other performers.”

He has sometimes been criticized for how much he borrowed from others, but that was not an issue until he became famous. At the time, as Van Ronk put it, “We all lived with our hands in each other’s pockets. You’d learn a new song or work out a new arrangement, and if it was any good you’d know because in a week or two everybody else would be doing it.”

In those first months a lot of people regarded Dylan as just another young folksinger with a particularly abrasive voice, and some are still baffled by his success. But others say he stood out immediately:

For Dylan, as for Pete Seeger, the attraction of folk music was that it was steeped in reality, in history, in profound experiences, ancient myths, and enduring dreams. It was not a particular sound or genre; it was a way of understanding the world and rooting the present in the past.

There was always a disconnect between the aesthetic of the hardcore folk scene and the marketing categories of the music business. Going

“I played all the folk songs with a rock ’n’ roll attitude,” Dylan recalled. “This is what made me different and allowed me to cut through all the mess and be heard.”

Among the neo-ethnic crowd, songwriting tended to be viewed with suspicion, in large part because it was associated with the Seeger-Weavers generation and pop-folk trends.

Within four months of arriving in New York he got a gig at the most prestigious showcase of the neo-ethnic scene, Gerdes Folk City, opening for the legendary John Lee Hooker, and a few months later his talents were recognized by another legend, the record producer John Hammond.

Shelton recalled that the Times piece was applauded by Van Ronk and Elliott, but “much of the Village music coterie reacted with jealousy, contempt, and ridicule.” When it was followed by a Columbia recording contract, “Dylan felt the sting of professional jealousy. He began to lose friends as fast as he had made them.”

Time magazine, in a cover story featuring Joan Baez, wrote: The tradition of Broonzy and Guthrie is being carried on by a large number of disciples, most notably a promising young hobo named Bob Dylan.

More to the point, neither Playboy nor Time would have been giving Dylan that kind of coverage if he had not been on a major national record label, and a lot of people couldn’t understand what he was doing there.

But Dylan’s problem was not that he had limited energies and needed to channel them; it was that he was exploding with ideas and needed opportunities to try them out.

He had been surrounded by leftists of various stripes since his Minneapolis days—there was no escaping that in urban Bohemia—and in August 1961 he met a seventeen-year-old named Suze Rotolo, who would be his companion, lover, and sometime muse for the next two years.

The melody was lilting and pretty, adapted from a nineteenth-century slave song that Odetta had recently recorded: “No More Auction Block for Me.”

They recognized the criticism as a badge of pride, proof that, rather than sounding like the callow college kids being marketed as folksingers, Dylan was in the same camp as Dave Van Ronk and the New Lost City Ramblers, evoking the authentic ethnic traditions of people like Lemon Jefferson and Roscoe Holcomb. But “Blowin’ in the Wind” was not the sort of song you might hear in a Texas juke joint or on a back porch in Kentucky. It was folksinger music.

The article continued: “Not since Charlie Chaplin piled up millions in the guise of a hapless hobo has there been a breed of entertainer to match today’s new professional folksingers in parlaying the laments of poverty into such sizable insurance against the experience of it.”

There were two distinctions that set him apart from previous folk stars: he was primarily a songwriter, and he had a lousy voice.

The review emphasized Dylan’s vocal deficiencies: “Sometimes he lapses into a scrawny Presleyan growl,” and “at its very best, his voice sounds as if it were drifting over the walls of a tuberculosis sanitarium—but that’s part of the charm.” He was the antithesis of a slick pop-folk warbler.

The image of Dylan as a songwriter who triumphed despite a lack of vocal and instrumental skills almost entirely supplanted his earlier reputation as a dynamic interpreter of rural roots music.

Baez was a dauntingly sincere artist, in Joan Didion’s phrase, “the Madonna of the disaffected.”

Grossman’s talents as a promoter were more than equaled by his backroom financial savvy, and a bedrock truth of the American music business is that performers reap the fame, but the money is in publishing. (In a holdover from the days of sheet music, a song’s publisher typically receives half of all royalty payments, though by 1960 the publisher’s sole contribution might have been to persuade the songwriter to sign a contract.)

Grossman had a unique deal with Witmark, receiving half the publisher’s royalties for any songwriter he brought to the company, and his management contract with Dylan—as with Odetta; Peter, Paul, and Mary; Ian and Sylvia; and the other acts he soon acquired—gave him 20 percent of the artist’s earnings, with an additional 5 percent for income from recordings. As a result he had a very strong interest in Dylan writing songs, recording them, and having them recorded by his other acts and anyone else who might care to join the party.

“Albert scared the shit out of people,” says Jonathan Taplin, who started as his assistant and went on to become a successful film producer. “He was the greatest negotiator in history.” Van Ronk recalled Grossman as an endlessly fascinating and amusing companion, but added, “He actually took a sort of perverse pleasure in being utterly unscrupulous.”

Dylan had a gut sense that the world was a mess and admired the idealism of Guthrie and Seeger, but his politics were a matter of feelings and personal observation rather than study or theory. “He was a populist,” Van Ronk said. “He was tuned in to what was going on—and much more than most of the Village crowd, he was tuned in not just to what was going on around the campuses, but also to what was going on around the roadhouses—but it was a case of sharing the same mood, not of having an organized political point of view.” Contrasting him with Phil Ochs, who had been a journalism major before taking up guitar, Rotolo noted, “Dylan was perceptive. He felt. He didn’t read or clip the papers. . . . It was all intuitive, on an emotional level.”

He was writing longer, more complex lyrics, and the British song forms provided useful patterns: “Girl from the North Country” and “Bob Dylan’s Dream” were based on Carthy’s versions of “Scarborough Fair” and “Lady Franklin’s Lament,” “With God on Our Side” on Dominic Behan’s “The Patriot Game,” and “Masters of War” on “Nottamun Town,” the Appalachian survival of a mysterious English song that retained echoes of ancient mummers’ rites. As

Dylan might recognize the value of that kind of self-abnegation and dedication, but he was repelled by the idea of anyone handing their mind over to any organization or ideology. He did not take part in rallies or marches and regularly denied that his songs expressed anything but his own experiences and feelings. When he presented himself as a little guy, one of the ordinary folk, his model was Woody, the quirky Okie bard who never really fit into any group and was rejected by the Communist Party as undisciplined and unreliable.

Dylan was more comfortable as a loner than as a spokesman, and when he made his strongest stand against censorship, in May 1963, it was right out of the pages of Bound for Glory. He had been booked to appear on the Ed Sullivan Show, America’s most popular variety program, but when they told him he couldn’t sing “Talkin’ John Birch Paranoid Blues,” he walked out, just as Woody had walked out of a showcase gig at Rockefeller Center’s Rainbow Room in the final scene of that book. In real life Woody was at the Rainbow Room as a member of the Almanac Singers, but when he reworked the story for his memoir he was by himself, one small guy standing up to a team of corporate bigwigs, and for anyone who loves that book it is a thrilling moment. Dylan re-created it in more public and significant circumstances, and his stand was hailed as a blow against the blacklist and cemented his reputation as Woody’s heir.

Though few reviews mentioned her, Wein recalled Baez as “not only the great discovery, but also the living symbol, of the first Newport Folk Festival.”

When critics attacked the Kingston Trio, the Brothers Four, or the New Christy Minstrels for having ordinary voices and instrumental skills and relying on a small repertoire of familiar songs, they were highlighting exactly what made those groups attractive to millions of kids across the United States: the idea that anyone could be part of the movement, not only as a spectator but as a participant.

That was what made Hootenanny so galling: it was simultaneously the most visible showcase for the folk revival and a prop of the conservative, conformist power structure the revivalists despised. Its

Tastes that a few years earlier had seemed esoteric were increasingly mainstream, which was great in some ways but disturbing in others—it was, of course, wonderful that the music had a larger audience, but it diluted the feeling of sharing something secret and precious, and there was every reason to fear that the mainstream would transform heartfelt art into mass-produced schlock.

One reason so many people cared so deeply about Seeger, Baez, and Dylan was that each managed to reach large audiences without seeming to compromise—and Dylan’s success was even more jarring than Seeger’s or Baez’s. They were both unique, committed artists, but also pleasant and reliable and, if they had been willing to relinquish their political commitments, could easily have joined the Hootenanny wave.

In musical terms, the contrast was striking. As Van Ronk put it, “Dylan, whatever he may have done as a writer, was very clearly in the neo-ethnic camp. He did not have a pretty voice, and he did his best to sing like Woody, or at least like somebody from Oklahoma or the rural South, and was always very rough and authentic-sounding.” With Baez, “it was all about the beauty of her voice,” and it was not just her: virtually all the female folk stars sang in styles influenced by classical bel canto. “Whereas the boys were intentionally roughing up their voices, the girls were trying to sound prettier and prettier, and more and more virginal . . . and that gave them a kind of crossover appeal to the people who were listening to Belafonte and the older singers, and to the clean-cut college groups.”

John Cohen argued that topical songs were actually less relevant than old ballads and fiddle tunes, since they “blind young people into believing they are accomplishing something . . . when, in fact, they are doing nothing but going to concerts, record stores, and parties.”

wrote that Bobby Zimmerman’s old acquaintances “chuckle at his back-country twang and attire and at the imaginative biographies they’ve been reading about him. They remember him as a fairly ordinary youth from a respectable family, perhaps a bit peculiar in his ways, but bearing little resemblance to the show business character he is today.” His parents told the reporter that Bobby had always written poems, but they were disturbed to see him acting like a hayseed, and his father provided an explanation his young fans could be expected to find particularly damning: “My son is a corporation and his public image is strictly an act.”

But—gotcha!—“A few blocks away, in one of New York’s motor inns, Mr. and Mrs. Abe Zimmerman of Hibbing, Minn., were looking forward to seeing their son sing at Carnegie Hall. Bobby had paid their way east and had sent them tickets.”

Baez and Dylan often irritated friends on the left with their unfocused politics, but in social terms they were solidly with the radicals.

It was a perfect revolution for young Americans raised on John Wayne and Marlon Brando movies, who dreamed of creating a new world through thrilling, heroic gestures.

in the summer of 1964 Dylan was still largely unknown to them. In a New Yorker profile later that year, Nat Hentoff indicated his “accelerating success” by noting that his first three LPs had cumulatively sold almost four hundred thousand copies. By comparison, Cash’s Ring of Fire LP, released shortly after Dylan’s second album, sold about five hundred thousand in its first year, which still didn’t come close to what Baez was selling, while Peter, Paul, and Mary were in a different league, regularly putting both albums and singles at the top of the charts.

the legendary Skip James, whose eerie falsetto and minor-keyed guitar style remain for many listeners the most profound blues on record.

It was the first time they had sung together, and Cash remembered it as the highlight of the festival. He had arrived a day late for his scheduled Friday appearances, almost blowing the gig, and was in the depths of his amphetamine addiction—Glover described him as “gaunt and twitchy, but real as hell”—and

To Seeger, folk music was defined by its relationship to communities and traditions: it was what nonprofessionals played in their homes or workplaces for their own amusement and the songs and music they handed down through that process to later generations. That did not mean it was better than the music of Beethoven or Gershwin, but it was different, and a big part of the difference was that it was shared, that no one owned or controlled it.

Buffy Sainte-Marie often repeated the story of singing “Universal Soldier” at the Gaslight Café and being complimented by a nice man who offered to help her by publishing the song, wrote a contract on a paper napkin, paid her a dollar, and acquired 50 percent of the fortune it made when it became an international hit—but

the singers shouted, “I get high! I get high! I get high!” Those were the days when dopers talked to each other in code, and Bob and his buddies were solid initiates, so they were thrilled to hear these merry limeys sneaking a hidden kick into a teen-pop chart hit. It was not until August, when Dylan met the Beatles in New York and suggested getting stoned together, that they explained they were actually singing “I can’t hide!”

In Paris he hung out with Hugues Aufray, who was translating his songs into French; drank good wines; ate in nice restaurants; and had a fling with Nico, the German fashion model and singer who would later join the Velvet Underground. From there he went to Berlin, then on to Greece with Nico in tow.

Unlike them, unlike the Kingston Trio, unlike Elvis or Duke Ellington or Hank Williams or Leopold Stokowski, Dylan and Seeger and Baez all walked onstage looking the same way they looked when they were walking down the street or hanging out with their friends—a conscious and striking departure not only from previous stage wear but from the suits, makeup, and neatly coifed hair that were still the norm for much of their audience.

Jagger recalled Dylan telling Keith Richards, “I could have written ‘Satisfaction’ but you couldn’t have written ‘Tambourine Man,’” and when the interviewer seemed shocked, he added, “That was just funny. It was great. . . . It’s true.”

The Byrds’ sound was a logical fusion of the Beatles and Peter, Paul, and Mary, and from the point of view of mainstream pop prognosticators it made the same sense as Chubby Checker recording a calypso twist. Hardcore folk fans were equally quick to make that connection, with a different implication: these people weren’t innovators, they were opportunists.

Most of the drugs had been around for a while—my father smoked marijuana with a group of medical students in 1933, taking careful notes on their revelations—but the elevation of drug use into a drug culture, and the equation of that culture with youth, music, and social change, was something new.

The song was “Like a Rolling Stone,” and though the version Dylan took into the studio on June 15 was a moody, seven-minute waltz, the next day they shifted to a 4/4 rock beat and, with the addition of Al Kooper on organ, cut the definitive version.

They recognized Dylan’s Sunday night set, when he “electrified one half of his audience and electrocuted the other,” as the “journalistic happening” of the 1965 Newport Festival.

Because this is folk music, however, one can only surmise that the quintet, electric guitars and all, are simple researchers dedicated to preserving the sound of the Beatles.”

In terms of record sales and name recognition, Dylan was still behind Peter, Paul, and Mary and roughly on a par with Baez, but in terms of current trends he was in another class. He had originally been scheduled for Thursday night, but there were so many complaints from fans who could not make that first show that he and Baez were switched, with her on Thursday and him on the final Sunday program.

In the legend of Newport 1965, Dylan’s Sunday night set was the culmination of a three-day battle between electric rebels and hidebound folk purists, and the opening volley was fired on Friday by the Paul Butterfield Blues Band.

To blues purists, the Chambers Brothers, Lightnin’ Hopkins—even, at a stretch, Bo Diddley and Chuck Berry—were authentic exponents of an ethnic folk culture, while Bloomfield, Butterfield, and Bishop, talented as they might be, were interpreters.

Lomax tried to push Grossman aside, or maybe it was Grossman who pushed Lomax. Either way, in seconds the portly prophet of tradition and the portly purveyor of mammon—“the two big bears,” in Maria Muldaur’s description—were throwing inept punches and rolling in the dust. “It was a perfect confrontation whose symbolism was lost on none of us,”

The audience has not heard their murmured interchange and waits quietly, then starts screaming and booing as Dylan unplugs his guitar and leaves the stage, followed by the other musicians. Yarrow steps to the microphone, still wearing his dark shades and looking tired and worried. The crowd is going wild. “Bobby was—” he begins, then pauses, summoning his resources: “Yes, he will do another tune, I’m sure, if you call him back.” Dylan’s set has lasted seventeen minutes, a bit over the normally allotted time, but included only three songs and a lot of dead space, and the crowd is full of people who came to Newport specifically to see him. There is no way they are going to let him get away that easily, and they meet Yarrow’s challenge with a frenzied mix of boos, applause, whistles, and shouts of “More!”

Whatever one’s opinion, the naysayers have some facts on their side: The band was underrehearsed, and even if one thinks the first two songs sound great, “Phantom Engineer” was a high-energy train wreck. Aside from the music, Dylan’s performance was halting and disorganized, and he made no attempt to engage with the audience, to excuse the problems, or to distract from the confusion. His set lasted roughly thirty-five minutes, longer than anyone else’s that night, but that included two minutes when he was offstage and eight when he was onstage tuning, waiting for the other guys to get ready, waiting for a new guitar, a capo, a harmonica, looking back over his shoulder, complaining, or simply strumming disjointedly and playing an occasional note on the harmonica.

Dylan told Anthony Scaduto, “I did not have tears in my eyes. I was just stunned and probably a little drunk.”

Phil Ochs gleefully suggested that the next year’s finale should “feature a Radio City Music Hall Rockette routine including janitors, drunken sailors, town prostitutes, clergy of all denominations, sanitation engineers, small time Rhode Island politicians, and a bewildered cab driver,” backed by “the beloved Mississippi John Hurt’s new electric band consisting of Skip James on bass, Son House on drums and Elizabeth Cotton on vibes being hissed and booed by the now neurotic ethnic enthusiasts.”

Seeger did not come to the party, but the following morning a young folk fan was eating breakfast at the Viking and noticed him sitting with his father, Charles, at the next table. “He was telling his father, who was hard of hearing, about what had happened and what he thought of Dylan, and he sort of leaned over, and these were his exact words: ‘I thought he had so much promise.’”

During the intermission that night, Theodore Bikel put it in a nutshell, telling a Broadside writer: “You don’t whistle in church—you don’t play rock and roll at a folk festival.” For that analogy to hold, Newport had to be the church: the quiet, respectable place where nice people knew how to act. Pete Seeger was the parson. The troubled fans were the decent, upstanding members of the community. And Dylan was the rebellious young man who whistled. Which was exactly what he had always been, and what Seeger had been, and what Newport had celebrated.

“The people” so loved by Pete Seeger are the mob so hated by Dylan. In the face of violence he has chosen to preserve himself alone. . . . And he defies everyone else to have the courage to be as alone, as unconnected, as unfeeling toward others, as he.

At the Philadelphia Folk Festival a few weeks later, Phil Ochs sang his attack on wishy-washy centrists, “Love Me, I’m a Liberal,” then pointed to a stream of water near the stage and said, “If Pete Seeger were here, he’d walk on it.” There was irony in these attacks, since Seeger remained a red-tainted pariah to conservatives and was barred from mainstream venues where Dylan and Ochs were welcome.

“Eve” was joined by dozens of discs with socially relevant themes, often set off with rudimentary harmonica fills.

Collins cut a Kooper-backed single of Dylan’s “I’ll Keep It with Mine”; Albert

Their caressing harmonies were a much easier sell than Dylan’s quirky rasp, and through the rest of the 1960s, while his albums sold in the mid-hundreds of thousands and the Rolling Stones only once cracked the million mark, each Simon and Garfunkel LP sold at least two or three million.

Some old-time Village regulars tried to hop the folk-rock train, but the main lesson most learned was that they were not Dylan.

The other reaction, which was even more damaging, was, “I’m gonna be next. All I have to do is find the right agent, the right record company, the right connections, and I can be another Bob Dylan!” Yeah, sure you could. All you had to do was write “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall”—for the first time. That was what Bobby did, and none of the rest of us did that. Even if everyone didn’t admit it, we all knew that he was the most talented of us.

Around the same time he told Robert Shelton, “My idea of a folk song is Jeannie Robertson or Dock Boggs. Call it historical-traditional music.” For him, folk songs were not mellow, feel-good music; they were a connection to a tangled, mythic past. “It comes about from legends, bibles, plagues,” he told Hentoff. “All these songs about roses growing out of people’s brains and lovers who are really geese and swans that turn into angels.” And, he added: “They’re not going to die.” Twenty years later he was still drawing that line: “Nowadays you go to see a folk singer—what’s the folk singer doin’? He’s singin’ all his own songs. That ain’t no folk singer. Folk singers sing those old folk songs, ballads.”

For northern liberals, Vietnam was a much more divisive issue than voting rights and integrated drinking fountains, and many supported Johnson’s effort to stem the spread of international Communism. Then,

On tour with Baez in 1963, he had been refused a hotel room because of his unkempt appearance and responded by composing “When the Ship Comes In.” The image was from Brecht’s “Pirate Jenny,” in which a hotel maid dreams of a ship of avenging pirates who will sweep ashore and slaughter the complacent, respectable bourgeoisie.

He released Bringing It All Back Home in the spring of 1965, Highway 61 Revisited that summer, and Blonde on Blonde a year later.

Dylan’s reception at Newport had so much resonance because he mattered to his audience in a way pop music had never mattered before, and the power of that message came not only from Dylan but from Newport, from the fact that he was booed at a beloved and respected musical gathering, by an audience of serious, committed young adults. The fans who booed him from Forest Hills to the Manchester Free Trade Hall over the next year were showing not only their anger at his capitulation to the mainstream but their solidarity with that first mythically angered cohort of true believers.

Inevitably, though, the technology made a difference: at Newport the audience was full of people with their own guitars and banjos, and when the official program was over the unofficial music-making continued, sounding very similar to what was happening onstage. Electric instruments, for better or worse, demanded amplifiers and electrical outlets and established a divide: players behind the amps, listeners in front. It was not impossible to sing along with a rock band, but it was irrelevant. As Dylan put it, Seeger made his listeners “feel like they matter and make sense to themselves and feel like they’re contributing to something,” while listening to a rock band “is like being a spectator at a football game. Pete is almost like a tribal medicine man, in the true sense of the word. Rock ’n’ roll performers aren’t. They’re just kind of working out other people’s fantasies.”

“Dylan is no apostle of the electronic age. Rather, he is a fifth-columnist from the past.”

-

Recalibrating thoughts on songwriting

Preamble

My Dylan and folk music obsession continues to progress. I was struck by the thought of how good something has to be to be “arranged”.

In his autobiography Dave van Ronk mentioned the sheer amount of creativity that goes into an arrangement of a well-known song. Related – I’ve been working on a bluegrass version of one of Leonard Cohen’s middle period songs.

The Gist

Then I listened to a bunch of Dylan outtakes and was struck by how much a song needed to be refined before it could be arranged. A lot of the earlier versions were good, but not much more than that. The final versions were instant classics that benefit the world.

-

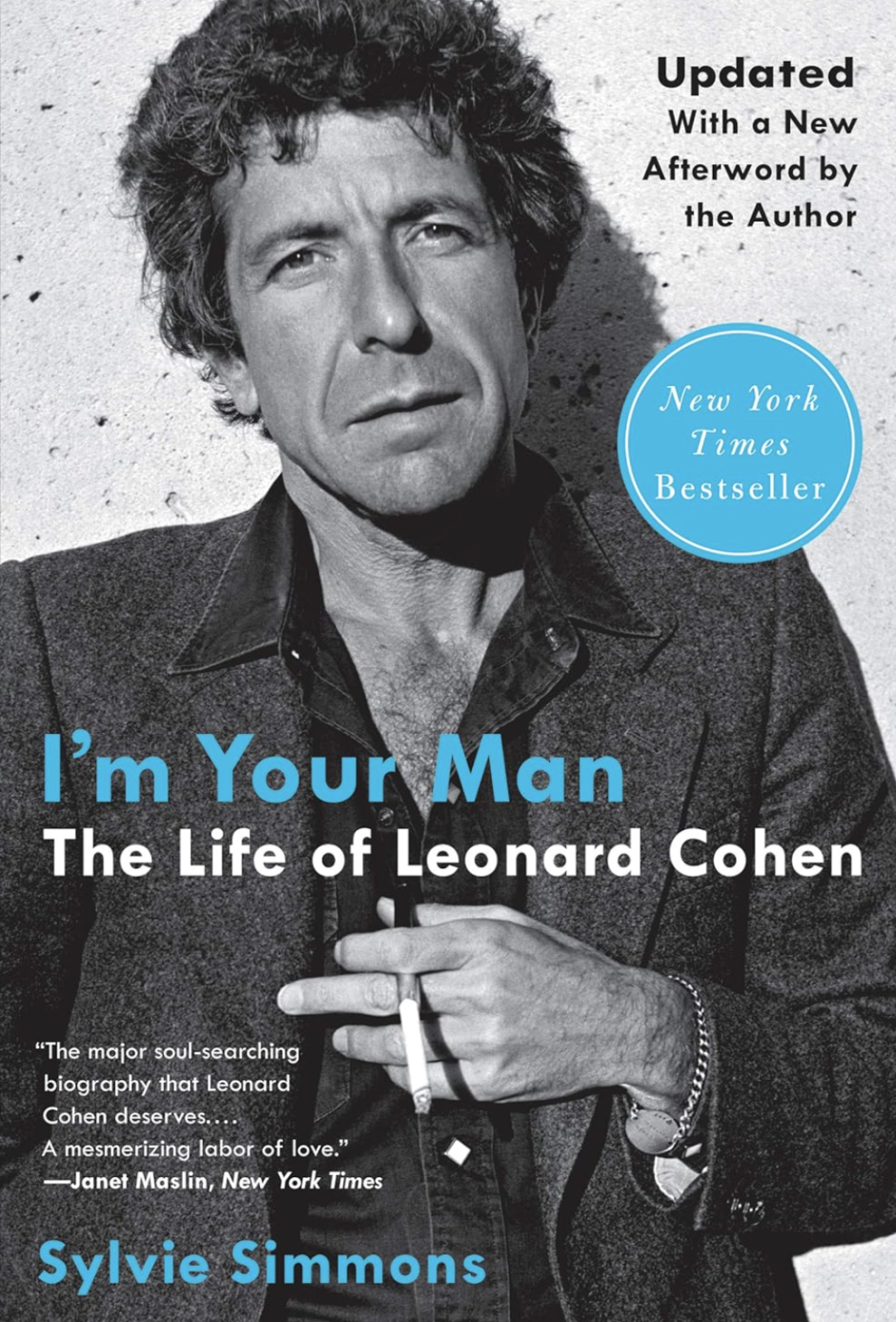

I’m Your Man: The Life of Leonard Cohen

This book succeeds as a biography better than almost any I’ve ever read. All Leonard Cohen questions are answered. All questions about the times in which he lived are answered. “What Leonard Cohen means to me (the author)” is touched upon lightly and then put down. As far as I can tell no relevant musical or poetic detail is omitted, including my long running question of “Why did he shift from guitar in the 1980s?”

Highly recommended for anyone into Leonard Cohen – well written and very informative.

Things that surprised me

- He spent much more time in the Buddhist monastery than I originally thought

- Far more drug use, especially amphetamines than I would have thought, especially later in life (most people grow out of that sort of thing as they get older, Leonard grew into it)

- His work ethic and perfectionism were quite impressive

- The reason that he moved from guitar based folk was not due to some artistic “growth” but a musical writer’s block regarding guitar accompaniment. His synthesizer accompaniment was no blocked so he rolled with that.

- His youth and his old age lasted for long periods of time, his middle age was quite short

Highlights

Many years later Edgar H. Cohen would go on to write Mademoiselle Libertine: A Portrait of Ninon de Lanclos, a biography published in 1970 of a seventeenth-century courtesan, writer and muse whose lovers included Voltaire and Molière, and who, after a period in a convent, emerged to establish a school where young French noblemen could learn erotic technique.

Leonard did not cry at the death of his father; he wept more when his dog Tinkie died a few years later. “I didn’t feel a profound sense of loss,” he said in a 1991 interview, “maybe because he was very ill throughout my entire childhood. It seemed natural that he died. He was weak and he died. Maybe my heart is cold.”

Chapter Two of the hypnotism manual might have been written as career advice to the singer and performer Leonard would become. It cautioned against any appearance of levity and instructed, “Your features should be set, firm and stern. Be quiet in all your actions. Let your voice grow lower, lower, till just above a whisper. Pause a moment or two. You will fail if you try to hurry.”

Since the age of thirteen Leonard had taken to going out late at night, two or three nights a week, wandering alone through the seedier streets of Montreal. Before the Saint Lawrence Seaway was built the city was a major port, the place where all the cargo destined for central North America went to be offloaded from oceangoing freighters and put on canal boats and taken up to the Great Lakes or sent by rail to the West. At night the city swarmed with sailors, longshoremen and passengers from the cruise ships that docked in the harbor, and welcoming them were countless bars, which openly flouted the law requiring that they close at three A.M.

Lorca was a dramatist and a collector of old Spanish folk songs as well as a poet, and his poems were dark, melodious, elegiac and emotionally intense, honest and at the same time self-mythologizing. He wrote as if song and poetry were part of the same breath. Through his love for Gypsy culture and his depressive cast of mind he introduced Leonard to the sorrow, romance and dignity of flamenco. Through his political stance he introduced Leonard to the sorrow, romance and dignity of the Spanish Civil War. Leonard was very pleased to meet them both.

Over the subsequent years, whenever interviewers would ask him what drew him to poetry, Leonard offered an earthier reason: getting women. Having someone confirm one’s beauty in verse was a big attraction for women, and, before rock ’n’ roll came along, poets had the monopoly. But in reality, for a boy of his age, generation and background, “everything was in my imagination,” Leonard said. “We were starved. It wasn’t like today, you didn’t sleep with your girlfriend. I just wanted to embrace someone.”

In the summer of 1950, when Leonard left once again for summer camp—Camp Sunshine in Sainte-Marguerite—he took the guitar with him. Here he would begin playing folk songs, and discover for the first time the instrument’s possibilities when it came to his social life. You were still going to summer camp at age fifteen? “I was a counselor.

There were a lot of the Wobbly songs—I don’t know if you know that movement? A Socialist international workers union. Wonderful songs. ‘There once was a union maid / Who never was afraid / Of goons and ginks and company finks / And deputy sheriffs that made the raid . . . No you can’t scare me I’m stickin’ with the union.’ Great song.”

Leonard was clearly enthused. Some fifty years after his stay at Camp Sunshine he could still sing the songbook by heart from beginning to end.* In

At the second lesson, the Spaniard started to teach Leonard the six-chord flamenco progression he had played the day before, and at the third lesson Leonard began learning the tremolo pattern. He practiced diligently, standing in front of a mirror, copying how the young man held the guitar when he played. His young teacher failed to arrive for their fourth lesson. When Leonard called the number of his boardinghouse, the landlady answered the phone. The guitar player was dead, she told him. He had committed suicide.

The streets around McGill University were named for august British men—Peel, Stanley, McTavish—its buildings constructed by solid, stony Scotsmen in solid Scottish stone.

Had someone told you the British Empire was run from McGill, you’d be forgiven for believing them; in September 1951, when Leonard started at McGill on his seventeenth birthday, it was the most perfect nineteenth-century city-within-a-city in North America.

The general attitude to bilingualism at that time was not a lot different, if less deity-specific, from that of the first female governor of Texas, Ma Ferguson: “If the English language was good enough for Jesus Christ, it’s good enough for everybody.”

Fraternities and presidencies might appear surprisingly pro-establishment for a youth who had shown himself to have Socialist tendencies and a poetic inclination, but Leonard, as Arnold Steinberg notes, “is not antiestablishment and never was, except that he has never done what the establishment does. But that doesn’t make him antiestablishment.

But in 1952, between his first and second years, Leonard formed his first band with two university friends, Mike Doddman and Terry Davis. The Buckskin Boys was a country and western trio (Mort had not yet taken up the banjo or it might have been a quartet), which set about cornering the Montreal square-dance market.

Mostly, though, he played guitar—alone, in the quadrangle, at the frat house, or anywhere there was a party. It wasn’t a performance; it was just something he did. Leonard with a guitar was as familiar a sight as Leonard with a notebook.

Leonard, even before he started to write his own stuff, was relentless. He would play a song, whether it was ‘Home on the Range’ or whatever, over and over and over all day, play it on his guitar and sing it. When he was learning a song he would play it thousands of times, all day, for days and days and weeks, the same song, over and over, fast and slow, faster, this and that. It would drive you crazy. It was the same when he started to write his own stuff. He still works that way. It still takes him four years to write a lyric because he’s written twenty thousand verses or something.”

That sense of a lost Eden, of something beautiful that did not work out or could not last, would be detectable in a good deal of Leonard’s work.

“I felt that what I wrote was beautiful and that beauty was the passport of all ideas,” Leonard would say in 1991.

Leonard liked the Beats. They did not return the sentiment. “I was writing very rhymed, polished verses and they were in open revolt against that kind of form, which they associated with the oppressive literary establishment. I felt close to those guys, and I later bumped into them here and there, although I can’t describe myself remotely as part of that circle.”10 Neither did he have any desire to join it. “I

or writing about himself, as he did when one professor, knowing when he was beaten, allowed Leonard to submit a term paper on Let Us Compare Mythologies.

He applied to the U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Indian Affairs in Washington, DC, for a teaching position on a reservation. The bureau, oddly, had little use for a Jewish poet from Montreal with electro-cycle turret lathe skills.

Recalls Aviva Layton, who went to Leonard’s first night with Irving to give moral support, “I don’t remember him reading poetry, I remember him singing and playing the guitar. He perched himself on a high, three-legged stool and he sang—his own songs. That magic that he had, whatever it was, you could see it there at these performances.”

Survival, in discussions of the mystery and motivations of Leonard Cohen, has tended to be left in the corner clutching an empty dance card while writers head for the more alluring sex, God and depression and haul them around the dance floor. There is no argument that between them these three have been a driving force in his life and work. But what served Leonard best was his survival instinct.

Leonard walked through the town, he noticed that there were no cars. Instead there were donkeys, with a basket hung on either side, lumbering up and down the steep cobblestone streets between the port and the Monastery of the Prophet Elijah. It might have been an illustration from a children’s Bible.

On a small island with few telephones and little electricity, therefore no television, the ferry provided their news and entertainment, and their contact with the outside world.

The ritual, routine and sparsity of this life satisfied him immensely. It felt monastic somehow, except this was a monk with benefits; the Hydra arts colony had beaten the hippies to free love by half a decade.

He and I both carry komboloi—Greek worry beads; only Greek men do that. The beads have nothing to do with religion at all—in fact one of the Ancient Greek meanings of the word is ‘wisdom beads,’ indicating that men once used them to meditate and contemplate.”

He quoted himself saying, in his familiar partly humorous, partly truthful fashion, “I shouldn’t be in Canada at all. I belong beside the Mediterranean. My ancestors made a terrible mistake. But I have to keep coming back to Montreal to renew my neurotic affiliations.”

In this drab, run-down part of the Lower East Side, it looked like somebody had bombed a rainbow.

Alighting in Aberdeen, Trocchi made his way to London, where he registered as a heroin addict with the National Health Service and obtained his drug legally.

Leonard had the assistance, or at least the companionship, of a variety of drugs. He had a particular liking for Maxiton, generically dexamphetamine, a stimulant known outside of pharmaceutical circles as speed. He also had a fondness for its sweet counterpoint Mandrax, a hypnotic sedative, part happy pill, part aphrodisiac, very popular in the UK. They were as handsome a pair of pharmaceuticals as a hardworking writer could wish to meet; better yet, in Europe they could still be bought over the counter. Providing backup was a three-part harmony of hashish, opium and acid (the last of these three still legal at that time in Europe and most of North America).

That same year, her former partner became the first black person to be imprisoned under Britain’s Race Relations Act—a statute originally passed to protect immigrants from racism—after calling for the shooting of any black woman seen with a white man; Bacal is white.

The end of De Freitas/X/Malik’s story came in 1975, when he was hanged for murder. The Trinidad government ignored pleas for clemency from people in the U.S., UK and Canada, many of them celebrities. They included Angela Davis, Dick Gregory, Judy Collins and Leonard Cohen.

Leonard also argued to keep the title. It would appeal, he wrote, to “the diseased adolescents who compose my public.”

He put the albums on, Nadel wrote, “to the chagrin of everyone” besides Leonard, who listened “intently, solemnly” and announced to the room “that he would become the Canadian Dylan.”

At his decree, their singer and songwriter Lou Reed, a short, young, Jewish New Yorker, shared the spotlight with a tall, blond German in her late twenties. Nico, said Lou Reed, “set some kind of standard for incredible-looking people.”

While Dylan was babysitting her son, Ari—the result of her brief affair with the French movie star Alain Delon—Dylan wrote the song “I’ll Keep It with Mine,” which he gave to Nico. When

“You’re Leonard Cohen, you wrote Beautiful Losers,” which nobody had read, it only sold a few copies in America. And it was Lou Reed.

Nico told Leonard she liked younger men and did not make an exception. Her young man du jour, her guitar player, was a fresh-faced singer-songwriter from Southern California, barely eighteen years old, named Jackson Browne. A surfer boy crossed with an angel, his natural good looks appeared unnatural alongside the cadaverous Warhol and his black-clad entourage.

bumped into Jim Morrison a couple of times but I did not know him well. And Hendrix—we actually jammed together one night in New York. I forget the name of the club, but I was there and he was there and he knew my song ‘Suzanne,’ so we kind of jammed on it.” You and Hendrix jammed on “Suzanne”? What did he do with it? “He was very gentle. He didn’t distort his guitar. It was just a lovely thing. I

With “Suzanne” being such a powerful song and Collins such an evangelical cheerleader for its writer, Leonard was getting attention too, including from John Hammond, the leading A & R man at America’s foremost record company, Columbia.

Leonard knew how he wanted to sound, or at least how he did not want to, but as an untrained musician he lacked the language to explain it. He could not play as well as the session musicians, so he found them intimidating.

In 1964 Joni quit art school to be a folksinger, moving to Toronto and the coffeehouses around which the folk scene revolved. In February 1965 she gave birth to a daughter, the result of an affair with a photographer. A few weeks later she married folksinger Chuck Mitchell and gave the baby up for adoption. The marriage did not last. Joni left, taking his name with her, and moved into Greenwich Village, where she was living alone in a small hotel room when she met Leonard.

Any close inspection of Mitchell’s songs pre- and post-Leonard would seem to indicate that he had some effect on her work. Over the decades, Leonard and Joni have remained friends.

“He was tentative and earnest, very unpolished,” says Montreal music critic Juan Rodriguez. Nancy Bacal concurs. “He was horrified, just frozen. He told me, looking out at these people, how could he just become this other person?

producer and music publisher named Jeff Chase whom Mary Martin thought might prove helpful was brought in, and somewhere in the process Leonard appeared to have somehow signed over the songs to him.

When Fields walked into the room, he found the two women “pasting sequins one at a time in a coloring book,” an activity pursued after the age of seven only if a person is on speed.

He was involved and yet not involved—which described his general dealings with the Warhol set. They were more to his taste than the hippie scene on the West Coast that had begun to infiltrate New York: “There seemed to be something flabby about the hippie movement. They pulled flowers out of public gardens. They put them in guns, but they also left their campsites in a mess. No self-discipline,” he said.

This time, when Leonard arrived at Studio B for the first session, there were no musicians waiting for him, just his young producer and the two union-mandated engineers. (“Producers could only talk,” says Simon. “Unless you were in the union, you were strictly forbidden from touching any equipment, mics, mixing board, etc.”)

Three weeks and four sessions later, Leonard nailed “So Long, Marianne,” a song he had recorded more than a dozen times with two producers and with two different titles. In total, since May 1967 Leonard had recorded twenty-five original compositions with John Hammond and John Simon. Ten of these songs made it onto Leonard’s debut album. Four would be revisited on his second and third albums, and two would appear as bonus tracks on the Songs of Leonard Cohen reissue in 2003 (“Store Room” and “Blessed Is the Memory”).

As my friend Leon Wieseltier said, ‘It has the delicious quality of doneness.’

one thing Leonard said he liked about Greece was that he could get Ritalin there—a stimulant widely used for both narcolepsy and hyperactivity—without a prescription. Crill told Leonard that he had stopped taking acid since some of the manufacturers starting cutting it with Ritalin. “Leonard said, ‘Oh, I really loved that.’ He said it was very good for focus.”

Said Leonard, “I always think of something Irving Layton said about the requirements for a young poet, and I think it goes for a young singer, too, or a beginning singer: ‘The two qualities most important for a young poet are arrogance and inexperience.’ It’s only some very strong self-image that can keep you going in a world that conspires to silence everyone.”

“Suzanne,” the opening song, appears to be a love song, but it is a most mysterious love song, in which the woman inspires a vision of Jesus, first walking on the water, then forsaken by his father, on the Cross. “So Long, Marianne,” likewise, begins as a romance, until we learn that the woman who protects him from loneliness also distracts him from his prayers, thereby robbing him of divine protection. The two women in “Sisters of Mercy,” since they are not his lovers, are portrayed as nuns. (Leonard wrote the song during a blizzard in Edmonton, Canada, after encountering two young girl backpackers in a doorway. He offered them his hotel bed and, when they fell straight to sleep, watched them from an armchair, writing, and played them the song the next morning when they woke.)

After his short promotional trip to London, Leonard returned to New York and the Chelsea. He checked into room 100 (which Sid Vicious and Nancy Spungen would later make notorious) and propped his guitar in the corner and put his typewriter on the desk.

Leonard thought Scientology, for all its snake oil, had “very good data.”9 He signed up for auditing.

Since Bob Johnston was, as always, busy in the studio, he sent Charlie Daniels to pick them up. In 1968 Daniels wasn’t the Opry-inducted, hard-core country star with the big beard and Stetson, but a songwriter and session musician—fiddle, guitar, bass and mandolin. Johnston

One night Daniels called Johnston and asked if he could get him out of jail—it was advance planning; Daniels was about to get into a fistfight with a club owner. Johnston hollered down the phone that he should “get the fuck out to Nashville,” and he did. Johnston had kept him busy ever since, playing on albums by Johnny Cash, Marty Robbins, Bob Dylan, and now Leonard Cohen.

Johnston taped Leonard singing ten songs. Five would appear on Songs from a Room; one would be put aside for the third album, Songs of Love and Hate; and four have never as yet been released: “Baby I’ve Seen You,” “Your Private Name,” “Breakdown” and “Just Two People”

Other singer-poets are obscure, but generally the feeling comes through that an attempt is being made to reach to a heart of meaning. But Cohen sings with such lack of energy that it’s pretty easy to conclude that if he’s not going to get worked up about it, why should we.”

In 1962, when Roshi was fifty-five, just a kid with a crazy dream, he left Japan for Los Angeles to establish the first Rinzai center in the U.S.

Then, “he locked himself in one of the suites for hours and listened to the music and read the books he had his chauffeur go out and buy of Leonard’s. He came out and said he at least felt I was leaving him for someone worthwhile.”

But Leonard no longer attended the Scientology Center. Disenchantment had set in, as well as anger that the organization had begun to exploit his name. Leonard had “gone clear”; he had a certificate confirming him as a “Senior Dianetic, Grade IV Release.”4 “I participated in all those investigations that engaged the imagination of my generation at that time,” said Leonard. “I even danced and sang with the Hare Krishnas—no robe, I didn’t join them, but I was trying everything.”

It was May 4, 1970, the day of the Kent State massacre in the U.S., and, as some kind of convoluted antiauthority peace gesture, Leonard decided to start the second half of the show by clicking his heels twice and giving the Nazi salute. He had come back onstage to lighted matches and a long standing ovation, but the mood changed instantly.

Leonard took Cornelius, Johnston and Donovan to meet a friend in London who—he told them—had the best acid anywhere. “It was called Desert Dust and it was like LSD-plus,” says Cornelius. “You had to take a needle—a pin was too big—and touch your tongue with this brown dust, and with as much as you could pick up on the end of that needle you were gone, sixteen hours, no reentry.” Ample supplies were purchased and consumed; it would get to where the tour manager made them all hold hands at the airport as they walked to the plane so that he would not lose anyone—“a big conga line,” Donovan says, “with everybody just singing along.”

A review of the show in Billboard described him as “nervous” and “lifeless.” Wrote Nancy Erlich, “He works hard to achieve that bloodless vocal, that dull, humorless quality of a voice speaking after death. And the voice does not offer comfort or wisdom; it expresses total defeat. His art is oppressive.”

“Leonard said, ‘I want to play mental asylums,’ ” says Johnston. And just like he’d done when Johnny Cash told him he wanted to play prisons, Johnston said, “Okay,” and “booked a bunch of them.” Despite appearances, the Henderson (closed now, due to funding cuts) was a pioneering hospital with an innovative approach to the treatment of personality disorders. It called itself a therapeutic community and the patients residents.

The artists who played that year included the Who, the Doors, Miles Davis, Donovan and Ten Years After. Leonard had the slot before last on the fifth and final day, after Jimi Hendrix and Joan Baez and before Richie Havens.

Tension had been rising at the festival for days. The promoters had expected a hundred and fifty thousand people but half a million more turned up, many with no intention of paying. Even

Thirty-nine years later the spellbinding performance was released, along with Lerner’s footage, on the CD/DVD Leonard Cohen: Live at the Isle of Wight 1970

Leonard’s depression begged to differ. Says Suzanne, “Of course, it can feel like a dark room with no doors. It’s a common experience of many people, especially with a creative nature, and the more spiritual the person, the closer to the tendency resembling what the church called acedia”—a sin that encompassed apathy in the practice of virtue and the loss of grace.

He was at the Chelsea, having what might have been a somber, one-man bachelor party.

Leonard tried to get in contact, but he says, “I was just too late.” She had killed herself three days before. Leonard was mentioned in her suicide note. He published her letter on the album sleeve, he said, because she had always wanted to be published and no one would do so.

Leonard said in 1974. “I am committed to the survival of the Jewish people”7), but also bravado, narcissism and, near the top of the list, desperation to get away. “Women,” he said, “only let you out of the house for two reasons: to make money or to fight a war,”8 and in his present state of mind dying for a noble cause—any cause—was better than this life he was living as an indentured artist and a caged man.

“Who by Fire” had been directly inspired by a Hebrew prayer sung on the Day of Atonement when the Book of Life was opened and the names read aloud of who will die and how. Leonard said he had first heard it in the synagogue when he was five years old, “standing beside my uncles in their black suits.”

“We were all kids. I was twenty-two and I had never played a concert before such a big audience, and I’ve never been on tour with a guy who’s revered like he was. In Europe Leonard was bigger than Dylan—all the shows were sold out—and he had the most sincere, devoted, almost nuts following.

Serious poetry lovers don’t get violent but, boy, there was some suicide watches going on, on occasion. There were people who Leonard meant life or death to. I’d see girls in the front row”—women outnumbered men three to one in the audiences, by Lissauer’s count—“openly weep for Leonard and they would send back letters and packages.

The only guy I’ve seen who drew better-looking women than Leonard Cohen was probably Charles Bukowski. These women were all dressed up in seventies style and hanging on Leonard’s every word, during the show and afterwards.”

Leonard was also hungry for hunger. This domestic life had caused him to put on weight and what he needed was to be empty. As he wrote in Beautiful Losers, “If I’m empty then I can receive, if I can receive it means it comes from somewhere outside of me, if it comes from outside of me I’m not alone. I cannot bear this loneliness . . .”—a loneliness deeper than anything that the ongoing presence of a woman and children could relieve.

John Miller replaced Lissauer as musical director, the rest of the band consisting of Sid McGinnis, Fred Thaylor and Luther Rix. Leonard’s new backing singers were Cheryl Barnes (who three years later would appear in the film of the musical Hair) and a nineteen-year-old Laura Branigan (who three years later would sign to Atlantic and become a successful solo pop artist).

“So,” says John Lissauer, “the famous missing album. I have the rough mixes but the master tapes just disappeared. Marty culled the two-inch tapes from both studios. He never returned my calls and Leonard didn’t return my calls. Maybe he was embarrassed. I didn’t find out what happened for twenty-five years. I heard this from a couple of different sources. Marty managed Phil Spector and Spector had not delivered on this big Warner Bros. deal; they got a huge advance, two million dollars, and Marty took his rather hefty percentage, but Phil didn’t produce any albums. So Warner Bros. go to Marty, ‘He comes up with an album or we get our money back.’ So Marty said, ‘I know what to do. Screw this Lissauer project, I’ll put Phil and Leonard together.’ ” Which is what he did.

His records were “Phil Spector” records, the artists and musicians merely bricks in his celebrated “Wall of Sound”—the name that was given to Spector’s epic production style. It required battalions of musicians all playing at the same time—horns bleeding into drums bleeding into strings bleeding into guitars—magnified through tape echo. With this technique Spector transformed pop ballads and R & B songs, like “Be My Baby,” “Da Doo Ron Ron” and “Unchained Melody” into dense, clamorous, delirious minisymphonies that captured in two and a half exquisite minutes the joy and pain of teenage love.

Leonard was dressed for work, wearing a suit and carrying a briefcase. He looked, Dan Kessel recalls, “like a suave, continental Dustin Hoffman.”

“In the final moment,” Leonard said, “Phil couldn’t resist annihilating me. I don’t think he can tolerate any other shadows in his darkness.”

after his initial misgivings about fatherhood he had taken to it seriously, and his friends say he was grief-stricken at being separated from