-

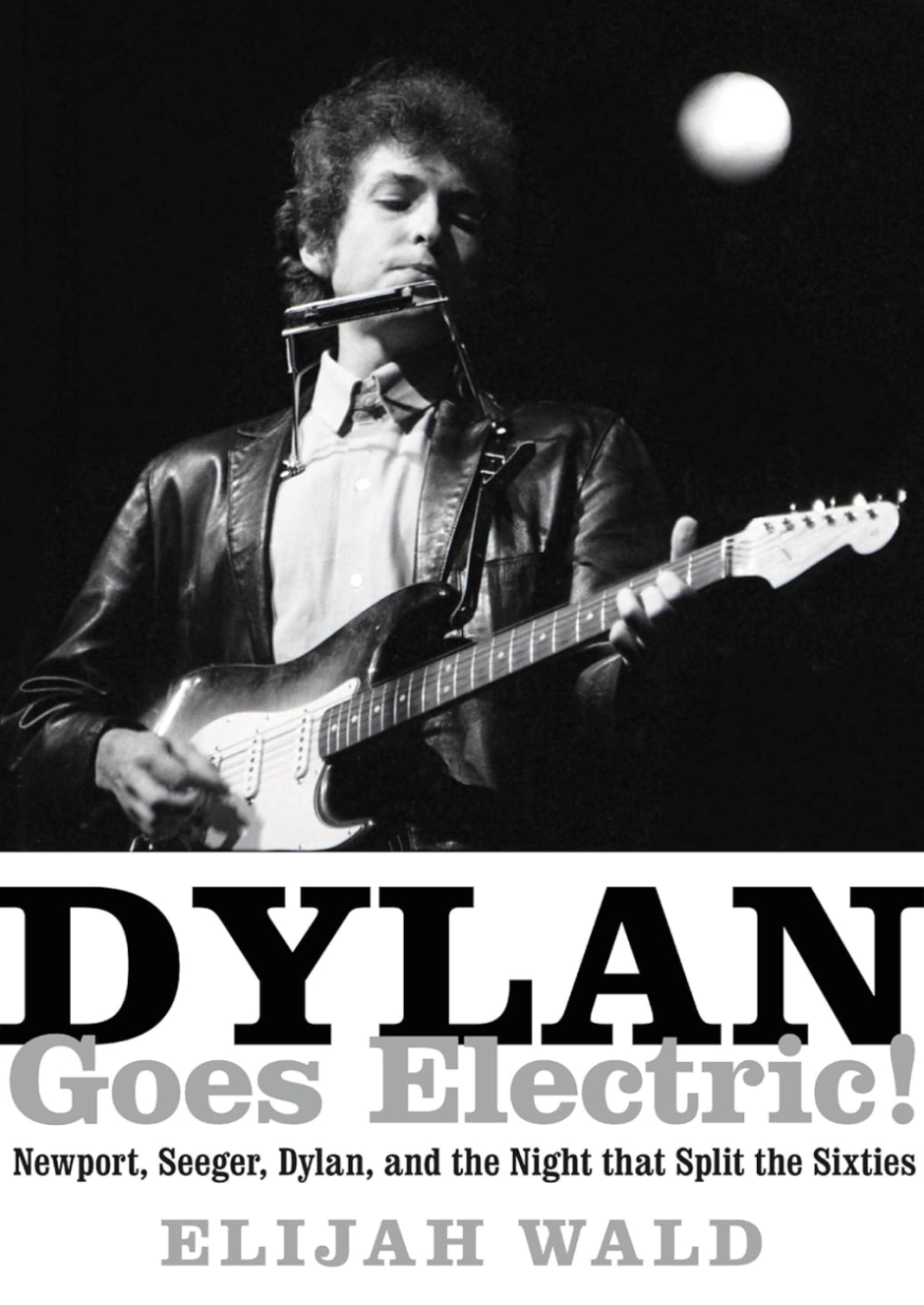

Dylan Goes Electric by Elijah Wald

The book in 3 sentences

An excellent history of the Greenwich Village folk scene in the late 1950s and early 1960s, American folk music in general and early Dylan in particular. It filled in a lot of gaps in my understanding of the music, the people and the time period. How so much musical genius could coalesce and enhance each other is a marvel to behold. It’s easy to forget how hard music was to come by in that time. These days you can just say something into the air and a song will start to play, but in the 1950s if you wanted to hear Appalachian ballads you had to actually go to Appalachia, listen to radio stations you probably could not get, or luck into a friend with an improbably rare record collection.

Greenwich Village being a nexus of folk music talent meant that the folk singers from all over America could just come and swap songs – basically switching from intellectual and musical high latency and low bandwidth musical environment to a low latency and high bandwidth musical environment.

There was also a buildup of talent in Greenwich Village, and then for whatever (not really that related) reason tastes and styles went in the folk music direction and there was a wealth of talent to choose from. The amount of folk music in the highest selling records of the time period surprised me quite a bit.

How I Discovered It

I watched the movie “A Complete Unknown”

Who Should Read It?

Anyone interested in the music or the time period.

How the Book Changed Me

- The primary changes were the ones mentioned above, the main one not mentioned so far is the role of Pete Seeger. I started the book thinking that the movie exaggerated his importance and probably combined several people into one character, but after reading the book, if anything the movie minimized his role in American folk music. He did a staggering amount of work for a staggering number of years just keeping folk music as folk music a going concern. Before it appears in the comments (ha!) yes – the Stalin’s Songbird title is appropriate but meaningless. Folk singer political opinions do not count.

Highlights

Seeger was a hard man to know and sometimes a hard man to like, but he was an easy man to admire, and he backed up his words and beliefs with his actions. Some people might think it was hokey to build that house with his own hands, the Harvard boy homesteading on a patch of prairie an hour and a half north of Manhattan.

In retrospect that legend often overshadowed his work, and it is easy to forget what the work was. This is particularly true because Seeger was first and foremost a live performer, and only a shadow of his art survives on recordings. That was fine with him—he always felt the recordings were just another way of getting songs and music out into the world. If you complimented him, he would suggest you listen to the people who inspired him, and a lot of us did and discovered Woody Guthrie, Lead Belly, Uncle Dave Macon, Bob Dylan, and hundreds of other artists whose music we often liked more than his.

Pete would quote his father, Charles Seeger: “The truth is a rabbit in a bramble patch. One can rarely put one’s hand upon it. One can only circle around and point, saying, ‘It’s somewhere in there.’”

There were myriad views and conceptions of the folk revival, but in general they can be divided into four basic strains: the encouragement of community music-making (amateurs picking up guitars and banjos and singing together with their friends); the preservation of songs and styles associated with particular regional or ethnic communities (the music of rural Appalachia, the Mississippi Delta, the western plains, the Louisiana Cajun country, the British Isles, Congo, or anywhere else with a vibrant vernacular culture); the celebration of “people’s music” and “folk culture” as an expression of a broader concept of the people or folk (linking peasant and proletarian musical traditions with progressive and populist political movements); and the growth of a professional performance scene in which a broad variety of artists were marketed as folksingers. People committed to one of those strains often tried to distance themselves from people identified with another—purists criticized popularizers, popularizers mocked purists—but they all overlapped and intertwined, and all flowed directly from Pete Seeger.

Seeger’s name was inherited from a German great-great-grandfather who immigrated to the United States in 1787, but most of his ancestors had come over from England in the early Colonial period. His parents were classical musicians, his mother a violinist and his father a pianist and musicologist. A photo from 1921 shows two-year-old Pete seated on his father’s lap as his parents play music in a dirt clearing between their homemade wooden trailer and a makeshift tent. They were trying to bring culture to the common people, touring in support of socialism and the populist dissemination of “good” music.

He was briefly home from one of a series of boarding schools, which led to Harvard, which he dropped out of at nineteen, moving to New York City to be a newspaper reporter.

He was acting on Woody’s exhortation to “vaccinate yourself right into the big streams and blood of the people,” and recalled that trip as an essential part of his education, later advising young fans to spend their summer vacations hitchhiking around the country, meeting ordinary folks and learning how to fend for themselves in unfamiliar territory.

That would always be Pete’s unique talent: no matter the audience, no matter the situation, he could get people singing.

explaining that in country cabins the only books you’d find were a Bible and an almanac, one to get you to the next world and the other to see you through this one.

Seeger had always been shy, and the philosophy of anonymous participation suited his nature as well as his political beliefs—though it caused some friction in the Almanac Singers, since he and most of the others felt their songs should be presented as anonymous, communal creations, while Guthrie wanted to be properly credited for his work.

Though often attacked as a “Communist front,” People’s Songs received little encouragement from the Party, which did not think folk songs were likely to appeal to urban proletarians and preferred to cultivate artists like Duke Ellington—Seeger recalled a Communist functionary telling him, “If you are going to work with the workers of New York City, you should be in the jazz field. Maybe you should play a clarinet.”

Mostly, though, he worked on the Bulletin, presented educational programs about folk music, and played at benefits, square dances, and community events like the Saturday morning “wing-dings” he held for kids in his Greenwich Village apartment.

He and Toshi were living in the basement of her parents’ house on MacDougal Street—her Japanese father and Virginian mother were committed radicals, so he fit right in—and Pete seems to have been happy with this situation, earning minimal pay, serving progressive causes, and, in his words, “congratulating myself on not going commercial.”

“On Top of Old Smoky” (on which Pete created a model for future sing-along leaders by speaking each line before the group sang, like a preacher “lining out” a hymn),

The Trio added a new, young, collegiate flavor and became the defining pop-folk group of the early 1960s. In 1961 the Highwaymen followed with “Michael, Row the Boat Ashore,” and the Tokens topped the charts by adding jungle drums and new lyrics to “Wimoweh” and retitling it “The Lion Sleeps Tonight.” The next year the Trio reached the Top 40 with Seeger’s “Where Have All the Flowers Gone”; Peter, Paul, and Mary got their first Top 10 hit with his “Hammer Song” (retitled “If I Had a Hammer”); and by 1965 the Byrds were at number one with his “Turn, Turn, Turn.”

Alan Lomax grumbled, “Peter looked at folk music as something to bring everybody in, whether they could sing or play in tune or anything like that.” Lomax, by contrast, wanted to focus attention on authentic proletarian artists and music. He was happy when a well-known entertainer was willing to help with that mission, whether it was the Weavers or a pop-jazz singer like Jo Stafford, but was annoyed that Pete encouraged urban amateurs to think they were carrying on folk traditions.

Pankake’s article underscored an essential fact: as the folk scene grew through the 1950s, it split into cliques that often bickered bitterly, but all came through Seeger, and while his recordings with the Weavers parented the pop-folk style, he was simultaneously parenting its traditionalist opponents.

As a result, although he was by far the most prolific recording artist on the folk scene, issuing six albums a year from 1954 through 1958, his playing and singing were often more workmanlike than thrilling, and it is easy to underestimate both his skills and his influence on other players.

To Seeger, everything was political. His belief in folk music fitted with his beliefs in democracy and communism, and if he was often troubled by the fruits of those beliefs, he remained undaunted, repeating, “All you can do in this world is try.” During the 1950s he did not record many explicitly political songs, in part due to Cold War paranoia but also because his years with the Almanac Singers and People’s Songs had made him aware of the limitations of that approach. He had hoped to support a singing labor movement, but found that “most union leaders could not see any connection between music and pork chops” and ruefully noted that by the late 1940s, “‘Which Side Are You On?’ was known in Greenwich Village but not in a single miner’s union local.” In the formulation of his biographer David Dunaway, he concluded that the most effective way to connect his music to his politics was by singing songs by the working class rather than writing songs for it.

But it was not the kind of music Pete wanted to be playing, and when the Weavers were hired to do a cigarette commercial a month and a half later, it was the final straw. As the group’s sole nonsmoker, he bowed to the democratic process and did the session, but quit immediately afterward, noting “the job was pure prostitution . . . [and] prostitution may be all right for professionals—but it’s a risky business for amateurs.”

By March 27, 1961, when Seeger’s case finally went to trial, the Kingston Trio’s “Tom Dooley” had kicked off a full-scale folk boom and the week’s top five albums included discs by the Trio, the Brothers Four, and the Limeliters. Folk ensembles accounted for ten of the thirteen best-selling albums by duos or groups, the Seegerless Weavers among them. Smoothly polished trios and quartets were still by far the most popular folk acts; although Joan Baez had released her first album in January and Billboard tipped it as a disc to watch, it was still just reaching the cognoscenti.

“Some jail will be a more joyous place if he lands there, and things will be bleaker on the outside.”

Seeger came of age in the Depression and never lost the sense that economic inequality was the root of humanity’s problems, that a vast majority of working people was threatened and subjugated by a tiny minority of rapacious capitalists, and that the only solution was to organize mass movements that would harness the people’s numbers to combat the oppressors’ wealth. Twenty years later, Dylan grew up in the most economically equitable era in American history. World War II had jump-started the US economy, and New Deal reforms meant that wealth was spread more evenly than ever before. When he wanted a car or a motorcycle, his father bought one for him, and a lot of his friends had cars or motorcycles too.

The battles of his youth were not organized political struggles; they were individual gestures of protest against the placid conformity of his elders and his less imaginative peers.

For a teenager bursting with unfocused energy, the country and western style was too restrained and also too widely available. He needed music that not only captured his imagination but set him apart, and found it in the R & B broadcasts he picked up on his bedside radio after the staid local programming had gone off the air. KTHS,

In the 1930s and 1940s radio had been dominated by national networks that beamed The Kraft Music Hall, Your Hit Parade, Amos ’n’ Andy, and The Lone Ranger into every home with electricity, but in the 1950s that role was taken over by television, and radio became a haven for local programming, ethnic programming, niche markets, and small sponsors.

In the 1930s Seeger had to travel to the Asheville Folk Festival to find the raw southern sounds that changed his life, but Dylan made the same journey without leaving his bedroom. To some extent that meant they had different relationships to the music: for Seeger it was inextricable from the communities that created it and the historical processes that shaped those communities, while for Dylan it was a private world of the imagination.

“Trying to make life special in Hibbing was a challenge. . . . Rock ’n’ roll made Bob and me feel special because we knew about something nobody else in Hibbing knew about. . . . We started losing interest in Elvis after he started becoming popular.”

In the right circles, obscure musical knowledge was social currency.

Kegan was a city boy whose regular singing partners included several African American teenagers, and they may have been the first black people Dylan met.

One way or another, he kept performing through his high school years.

Bob’s main instrument in this period seems to have been piano,

Aside from music, his other passion was movies—his uncle owned the local theater, so he could go as often as he wanted—and friends recalled him being particularly fascinated by Rebel Without a Cause, watching it over and over and buying a red jacket like James Dean’s character wore.

Not only was Dandy playing the right kind of records, when Bob and Bucklen inquired about him it turned out that he was African American—in Bucklen’s estimate “the only black guy within fifty miles.” That alone would have been enough to fascinate Bob.

Like many grown-ups in the R & B business, he regarded what he played on the radio as a compromise with the crude tastes of a mass public and preferred the intricate explorations of cool jazz and hard bop: Bucklen remembers him saying, “I like blues. I like rock music. But there’s no depth to it like jazz.”

an uncle—gave him an album of Lead Belly 78s. The next day he called Bucklen: “Bob almost shouted over the phone: ‘I’ve discovered something great! You got to come over here!’”

A teenager who disdained Elvis Presley as a pale imitation of Clyde McPhatter and got excited about Lead Belly was not going to have his world changed by the Kingston Trio.

Belafonte had originally modeled himself on Josh White, the black guitarist and singer from South Carolina who made rural blues palatable to New York cabaret audiences, then branched out into left-wing topical songs and Anglo-American ballads.

For a young musician who had trouble keeping bands together, there was an obvious appeal to music that could be played solo,

Odetta’s rich blend of bel canto and blues provided a connection to the artists Dylan already loved. If his voice sounded nothing like hers, that was hardly a barrier for someone who had previously modeled himself on Little Richard, and he arrived in Minneapolis with a repertoire largely drawn from her records: “Santy Anno,” “Muleskinner Blues,” “Jack o’ Diamonds,” “’Buked and Scorned,” “Payday at Coal Creek,” “Water Boy,” “Saro Jane,” and his first Woody Guthrie songs, “Pastures of Plenty” and “This Land Is Your Land”—the two Odetta had recorded.

judging by what survives on early tapes his second-strongest influence was yet another classically trained black folksinger, Leon Bibb,

Dylan was also thinking more professionally than most people on the scene.

He was naturally shy, but performing brought something out in him: “I could never sit in a room and just play all by myself,” he wrote. “I needed to play for people and all the time.” It was a way of relating to his new acquaintances, but also in some respects a way of shutting them out, and not everyone was supportive. “You’d go to a party and Bob would get a chair and move right into the center of the room and start singing,” Weber recalled. “If you didn’t want to listen, you got the hell out of the room, and I resented it.”

He stopped going to classes in his first semester and instead hung out in coffeehouses, bars, and friends’ apartments, soaking up conversation, music, books, and the Bohemian culture that had been so lacking in Hibbing.

They had mistaken commercial pap for authentic folk art, and it was their duty to rescue other innocents who had been similarly beguiled.

But Dylan was enthralled and inspired: when Pankake went out of town for a couple of weeks he helped himself to a bundle of records, and his current girlfriend, Bonnie Beecher, recalled him playing the Elliott albums, one after another, insisting that she recognize their brilliance: “Literally, you are in this room until you’ve heard them all, and you get it.”

Guthrie exerted a strong influence on both men, but they were also linked in other ways—both Jewish, middle-class, introverted loners who reinvented themselves as mythic wandering minstrels. Woody was an inspiration as much for his anarchic independence as for his specific musical skills, and although they sang dozens of Guthrie’s songs, that was almost an afterthought.

The Guthrie of Bound for Glory is a drifting hobo folksinger, picking up songs wherever he goes, sometimes improvising a lyric to suit a particular situation, but in general singing the familiar songs of ordinary working people. The real Guthrie spent a lot of time at a typewriter but sang a similar range of material, and on records, radio, and stage performances he showed no preference for his own compositions. For Dylan, Guthrie was exciting as a singer, player, and songwriter, but most of all as a man who lived life on his own terms. Given how large Guthrie has loomed in Dylan’s biographies, one of the most striking things about the surviving tapes of that year and a half in Minneapolis is how little Guthrie material is on them: a scant five songs, at least four of which Dylan had learned from other people’s recordings.

Nelson remembered Dylan changing instantly and dramatically after hearing those first Jack Elliott albums: “He came back in a day, or two at the most, and . . . from being a crooner basically, nothing special . . . he came back and sounded like he did on the first Columbia record.”

Little Richard and Odetta had been inspirational models, but Guthrie was more than just an exciting musician: he was a storyteller, a legend, and that fall he seems to have become a fixation.

a bunch of Woody’s letters from the hospital in New Jersey where he had been confined since the mid-1950s

Bob Dylan arrived in New York in January 1961 and headed to Greenwich Village, where he introduced himself to the local scene by playing a couple of songs at a coffeehouse on MacDougal Street.

in any case within that first week he met Guthrie, sang for him, and established himself as one of the few young performers who had a direct connection to Woody, not only as a legend but as a person.

More than that, he established himself with the New York folk crowd as a new incarnation of the Woody who had rambled out of the West twenty years earlier.

“There were detractors who accused Bob of being a Woody Guthrie imitator,” says Tom Paxton, a singer from Oklahoma who had arrived in the Village a year or so earlier. “But that was silly on the face of it, because Jack Elliott was a more conscious Woody clone than Bob ever was. When Bob sang Woody Guthrie songs it was very distinctive, but Bob sang like Bob right from the beginning.” Seeger agreed: “He didn’t mold himself upon Woody Guthrie. He was influenced by him. But he was influenced by a lot of people. He was his own man, always.”

Dylan loved Guthrie’s songs and cared about visiting him and singing for him, and some people close to Woody felt that Dylan established a stronger connection than any of the other young singers who made the pilgrimage.

Anyone hoping to understand the cultural upheavals of the 1960s has to recognize the speed with which antiestablishment, avant-garde, and grass-roots movements were coopted, cloned, and packaged into saleable products and how unexpected, confusing, and threatening that was for people who were sincerely trying to find new ways to understand the world or to make it a better place.

In terms of folk music in the early 1960s, it seemed pretty clear what kind of far-out was selling. “Rockless, roll-less and rich, the Kingston Trio by themselves now bring in 12% of Capitol’s annual sales, have surpassed Capitol’s onetime Top Pop Banana Frank Sinatra,”

In 1961 the Trio was the best-selling group in the United States, accounting for seven of Billboard magazine’s hundred top LPs. Harry Belafonte had three, the Limeliters had one,

Normal people might find it amusing to visit the Café Bizarre or the Wha? and see the weirdos in their native habitat, but the Kingston Trio was not only more polished and entertaining; they were also more honest: as Dave Guard said, “Why should we try to imitate Leadbelly’s inflections when we have so little in common with his background and experience?” The Bohemians were a bunch of poseurs who dressed badly, listened to screechy music, and were at best ridiculous and often frankly annoying. Of course, the Bohemians saw the situation rather differently: to them, the Trio and its fans were a bunch of empty-headed conformists marching in lockstep to the drumbeat of Madison Avenue and the Cold War military-industrial complex, and any effort to succeed on the commercial folk scene represented a compromise with a corporate culture that was bland, retrograde, and evil—the culture of blacklisting, segregation, and nuclear annihilation.

In 1963, Dylan’s girlfriend Suze Rotolo was told that her cousin’s husband, a career army officer, had lost a promotion that required security clearance because she was pictured with Dylan on the cover of his Freewheelin’ album,

Through most of the 1950s serious fans drew a distinction between authentic folksingers, who played the traditional music of their communities, and “singers of folk songs” like Seeger, Burl Ives, Richard Dyer-Bennett, and Odetta, who performed material collected in those communities but had not grown up in the culture.

Van Ronk, a leading figure in this group, later dubbed them the “neo-ethnics.” Some played old-time hillbilly music, some played blues, some sang medieval ballads, and there were lots of other flavors in the mix:

Music was permitted in the park from noon till five, and if you weren’t sated by then there would be a hootenanny and concert that evening at the American Youth Hostels building on Eighth Street. Then serious pickers and singers would convene at 190 Spring Street, where several musicians had apartments, or in various other lofts, basements, and walk-ups around the Village or Bowery, and the playing would continue till dawn. In terms of hearing new songs and styles, meeting other musicians, and building skills and repertoire, the parties were at least as important as the clubs and coffeehouses. The Village musicians all learned from one another and were each other’s most important audience.

They reshaped songs and arrangements to fit their tastes and talents, but always within the musical languages of the rural South, and within three years had recorded six albums for Folkways and spawned imitators across the country.

But music was always at the heart of it, and soon Dylan was playing decent fingerstyle guitar and singing a lot more blues.

Eric Von Schmidt was a painter, guitarist, and the uproarious Bohemian godfather of the Harvard Square scene, combining Van Ronk’s devotion to old jazz and blues with Elliott’s anarchic enthusiasm.

“You heard records where you could, but mostly you heard other performers.”

He has sometimes been criticized for how much he borrowed from others, but that was not an issue until he became famous. At the time, as Van Ronk put it, “We all lived with our hands in each other’s pockets. You’d learn a new song or work out a new arrangement, and if it was any good you’d know because in a week or two everybody else would be doing it.”

In those first months a lot of people regarded Dylan as just another young folksinger with a particularly abrasive voice, and some are still baffled by his success. But others say he stood out immediately:

For Dylan, as for Pete Seeger, the attraction of folk music was that it was steeped in reality, in history, in profound experiences, ancient myths, and enduring dreams. It was not a particular sound or genre; it was a way of understanding the world and rooting the present in the past.

There was always a disconnect between the aesthetic of the hardcore folk scene and the marketing categories of the music business. Going

“I played all the folk songs with a rock ’n’ roll attitude,” Dylan recalled. “This is what made me different and allowed me to cut through all the mess and be heard.”

Among the neo-ethnic crowd, songwriting tended to be viewed with suspicion, in large part because it was associated with the Seeger-Weavers generation and pop-folk trends.

Within four months of arriving in New York he got a gig at the most prestigious showcase of the neo-ethnic scene, Gerdes Folk City, opening for the legendary John Lee Hooker, and a few months later his talents were recognized by another legend, the record producer John Hammond.

Shelton recalled that the Times piece was applauded by Van Ronk and Elliott, but “much of the Village music coterie reacted with jealousy, contempt, and ridicule.” When it was followed by a Columbia recording contract, “Dylan felt the sting of professional jealousy. He began to lose friends as fast as he had made them.”

Time magazine, in a cover story featuring Joan Baez, wrote: The tradition of Broonzy and Guthrie is being carried on by a large number of disciples, most notably a promising young hobo named Bob Dylan.

More to the point, neither Playboy nor Time would have been giving Dylan that kind of coverage if he had not been on a major national record label, and a lot of people couldn’t understand what he was doing there.

But Dylan’s problem was not that he had limited energies and needed to channel them; it was that he was exploding with ideas and needed opportunities to try them out.

He had been surrounded by leftists of various stripes since his Minneapolis days—there was no escaping that in urban Bohemia—and in August 1961 he met a seventeen-year-old named Suze Rotolo, who would be his companion, lover, and sometime muse for the next two years.

The melody was lilting and pretty, adapted from a nineteenth-century slave song that Odetta had recently recorded: “No More Auction Block for Me.”

They recognized the criticism as a badge of pride, proof that, rather than sounding like the callow college kids being marketed as folksingers, Dylan was in the same camp as Dave Van Ronk and the New Lost City Ramblers, evoking the authentic ethnic traditions of people like Lemon Jefferson and Roscoe Holcomb. But “Blowin’ in the Wind” was not the sort of song you might hear in a Texas juke joint or on a back porch in Kentucky. It was folksinger music.

The article continued: “Not since Charlie Chaplin piled up millions in the guise of a hapless hobo has there been a breed of entertainer to match today’s new professional folksingers in parlaying the laments of poverty into such sizable insurance against the experience of it.”

There were two distinctions that set him apart from previous folk stars: he was primarily a songwriter, and he had a lousy voice.

The review emphasized Dylan’s vocal deficiencies: “Sometimes he lapses into a scrawny Presleyan growl,” and “at its very best, his voice sounds as if it were drifting over the walls of a tuberculosis sanitarium—but that’s part of the charm.” He was the antithesis of a slick pop-folk warbler.

The image of Dylan as a songwriter who triumphed despite a lack of vocal and instrumental skills almost entirely supplanted his earlier reputation as a dynamic interpreter of rural roots music.

Baez was a dauntingly sincere artist, in Joan Didion’s phrase, “the Madonna of the disaffected.”

Grossman’s talents as a promoter were more than equaled by his backroom financial savvy, and a bedrock truth of the American music business is that performers reap the fame, but the money is in publishing. (In a holdover from the days of sheet music, a song’s publisher typically receives half of all royalty payments, though by 1960 the publisher’s sole contribution might have been to persuade the songwriter to sign a contract.)

Grossman had a unique deal with Witmark, receiving half the publisher’s royalties for any songwriter he brought to the company, and his management contract with Dylan—as with Odetta; Peter, Paul, and Mary; Ian and Sylvia; and the other acts he soon acquired—gave him 20 percent of the artist’s earnings, with an additional 5 percent for income from recordings. As a result he had a very strong interest in Dylan writing songs, recording them, and having them recorded by his other acts and anyone else who might care to join the party.

“Albert scared the shit out of people,” says Jonathan Taplin, who started as his assistant and went on to become a successful film producer. “He was the greatest negotiator in history.” Van Ronk recalled Grossman as an endlessly fascinating and amusing companion, but added, “He actually took a sort of perverse pleasure in being utterly unscrupulous.”

Dylan had a gut sense that the world was a mess and admired the idealism of Guthrie and Seeger, but his politics were a matter of feelings and personal observation rather than study or theory. “He was a populist,” Van Ronk said. “He was tuned in to what was going on—and much more than most of the Village crowd, he was tuned in not just to what was going on around the campuses, but also to what was going on around the roadhouses—but it was a case of sharing the same mood, not of having an organized political point of view.” Contrasting him with Phil Ochs, who had been a journalism major before taking up guitar, Rotolo noted, “Dylan was perceptive. He felt. He didn’t read or clip the papers. . . . It was all intuitive, on an emotional level.”

He was writing longer, more complex lyrics, and the British song forms provided useful patterns: “Girl from the North Country” and “Bob Dylan’s Dream” were based on Carthy’s versions of “Scarborough Fair” and “Lady Franklin’s Lament,” “With God on Our Side” on Dominic Behan’s “The Patriot Game,” and “Masters of War” on “Nottamun Town,” the Appalachian survival of a mysterious English song that retained echoes of ancient mummers’ rites. As

Dylan might recognize the value of that kind of self-abnegation and dedication, but he was repelled by the idea of anyone handing their mind over to any organization or ideology. He did not take part in rallies or marches and regularly denied that his songs expressed anything but his own experiences and feelings. When he presented himself as a little guy, one of the ordinary folk, his model was Woody, the quirky Okie bard who never really fit into any group and was rejected by the Communist Party as undisciplined and unreliable.

Dylan was more comfortable as a loner than as a spokesman, and when he made his strongest stand against censorship, in May 1963, it was right out of the pages of Bound for Glory. He had been booked to appear on the Ed Sullivan Show, America’s most popular variety program, but when they told him he couldn’t sing “Talkin’ John Birch Paranoid Blues,” he walked out, just as Woody had walked out of a showcase gig at Rockefeller Center’s Rainbow Room in the final scene of that book. In real life Woody was at the Rainbow Room as a member of the Almanac Singers, but when he reworked the story for his memoir he was by himself, one small guy standing up to a team of corporate bigwigs, and for anyone who loves that book it is a thrilling moment. Dylan re-created it in more public and significant circumstances, and his stand was hailed as a blow against the blacklist and cemented his reputation as Woody’s heir.

Though few reviews mentioned her, Wein recalled Baez as “not only the great discovery, but also the living symbol, of the first Newport Folk Festival.”

When critics attacked the Kingston Trio, the Brothers Four, or the New Christy Minstrels for having ordinary voices and instrumental skills and relying on a small repertoire of familiar songs, they were highlighting exactly what made those groups attractive to millions of kids across the United States: the idea that anyone could be part of the movement, not only as a spectator but as a participant.

That was what made Hootenanny so galling: it was simultaneously the most visible showcase for the folk revival and a prop of the conservative, conformist power structure the revivalists despised. Its

Tastes that a few years earlier had seemed esoteric were increasingly mainstream, which was great in some ways but disturbing in others—it was, of course, wonderful that the music had a larger audience, but it diluted the feeling of sharing something secret and precious, and there was every reason to fear that the mainstream would transform heartfelt art into mass-produced schlock.

One reason so many people cared so deeply about Seeger, Baez, and Dylan was that each managed to reach large audiences without seeming to compromise—and Dylan’s success was even more jarring than Seeger’s or Baez’s. They were both unique, committed artists, but also pleasant and reliable and, if they had been willing to relinquish their political commitments, could easily have joined the Hootenanny wave.

In musical terms, the contrast was striking. As Van Ronk put it, “Dylan, whatever he may have done as a writer, was very clearly in the neo-ethnic camp. He did not have a pretty voice, and he did his best to sing like Woody, or at least like somebody from Oklahoma or the rural South, and was always very rough and authentic-sounding.” With Baez, “it was all about the beauty of her voice,” and it was not just her: virtually all the female folk stars sang in styles influenced by classical bel canto. “Whereas the boys were intentionally roughing up their voices, the girls were trying to sound prettier and prettier, and more and more virginal . . . and that gave them a kind of crossover appeal to the people who were listening to Belafonte and the older singers, and to the clean-cut college groups.”

John Cohen argued that topical songs were actually less relevant than old ballads and fiddle tunes, since they “blind young people into believing they are accomplishing something . . . when, in fact, they are doing nothing but going to concerts, record stores, and parties.”

wrote that Bobby Zimmerman’s old acquaintances “chuckle at his back-country twang and attire and at the imaginative biographies they’ve been reading about him. They remember him as a fairly ordinary youth from a respectable family, perhaps a bit peculiar in his ways, but bearing little resemblance to the show business character he is today.” His parents told the reporter that Bobby had always written poems, but they were disturbed to see him acting like a hayseed, and his father provided an explanation his young fans could be expected to find particularly damning: “My son is a corporation and his public image is strictly an act.”

But—gotcha!—“A few blocks away, in one of New York’s motor inns, Mr. and Mrs. Abe Zimmerman of Hibbing, Minn., were looking forward to seeing their son sing at Carnegie Hall. Bobby had paid their way east and had sent them tickets.”

Baez and Dylan often irritated friends on the left with their unfocused politics, but in social terms they were solidly with the radicals.

It was a perfect revolution for young Americans raised on John Wayne and Marlon Brando movies, who dreamed of creating a new world through thrilling, heroic gestures.

in the summer of 1964 Dylan was still largely unknown to them. In a New Yorker profile later that year, Nat Hentoff indicated his “accelerating success” by noting that his first three LPs had cumulatively sold almost four hundred thousand copies. By comparison, Cash’s Ring of Fire LP, released shortly after Dylan’s second album, sold about five hundred thousand in its first year, which still didn’t come close to what Baez was selling, while Peter, Paul, and Mary were in a different league, regularly putting both albums and singles at the top of the charts.

the legendary Skip James, whose eerie falsetto and minor-keyed guitar style remain for many listeners the most profound blues on record.

It was the first time they had sung together, and Cash remembered it as the highlight of the festival. He had arrived a day late for his scheduled Friday appearances, almost blowing the gig, and was in the depths of his amphetamine addiction—Glover described him as “gaunt and twitchy, but real as hell”—and

To Seeger, folk music was defined by its relationship to communities and traditions: it was what nonprofessionals played in their homes or workplaces for their own amusement and the songs and music they handed down through that process to later generations. That did not mean it was better than the music of Beethoven or Gershwin, but it was different, and a big part of the difference was that it was shared, that no one owned or controlled it.

Buffy Sainte-Marie often repeated the story of singing “Universal Soldier” at the Gaslight Café and being complimented by a nice man who offered to help her by publishing the song, wrote a contract on a paper napkin, paid her a dollar, and acquired 50 percent of the fortune it made when it became an international hit—but

the singers shouted, “I get high! I get high! I get high!” Those were the days when dopers talked to each other in code, and Bob and his buddies were solid initiates, so they were thrilled to hear these merry limeys sneaking a hidden kick into a teen-pop chart hit. It was not until August, when Dylan met the Beatles in New York and suggested getting stoned together, that they explained they were actually singing “I can’t hide!”

In Paris he hung out with Hugues Aufray, who was translating his songs into French; drank good wines; ate in nice restaurants; and had a fling with Nico, the German fashion model and singer who would later join the Velvet Underground. From there he went to Berlin, then on to Greece with Nico in tow.

Unlike them, unlike the Kingston Trio, unlike Elvis or Duke Ellington or Hank Williams or Leopold Stokowski, Dylan and Seeger and Baez all walked onstage looking the same way they looked when they were walking down the street or hanging out with their friends—a conscious and striking departure not only from previous stage wear but from the suits, makeup, and neatly coifed hair that were still the norm for much of their audience.

Jagger recalled Dylan telling Keith Richards, “I could have written ‘Satisfaction’ but you couldn’t have written ‘Tambourine Man,’” and when the interviewer seemed shocked, he added, “That was just funny. It was great. . . . It’s true.”

The Byrds’ sound was a logical fusion of the Beatles and Peter, Paul, and Mary, and from the point of view of mainstream pop prognosticators it made the same sense as Chubby Checker recording a calypso twist. Hardcore folk fans were equally quick to make that connection, with a different implication: these people weren’t innovators, they were opportunists.

Most of the drugs had been around for a while—my father smoked marijuana with a group of medical students in 1933, taking careful notes on their revelations—but the elevation of drug use into a drug culture, and the equation of that culture with youth, music, and social change, was something new.

The song was “Like a Rolling Stone,” and though the version Dylan took into the studio on June 15 was a moody, seven-minute waltz, the next day they shifted to a 4/4 rock beat and, with the addition of Al Kooper on organ, cut the definitive version.

They recognized Dylan’s Sunday night set, when he “electrified one half of his audience and electrocuted the other,” as the “journalistic happening” of the 1965 Newport Festival.

Because this is folk music, however, one can only surmise that the quintet, electric guitars and all, are simple researchers dedicated to preserving the sound of the Beatles.”

In terms of record sales and name recognition, Dylan was still behind Peter, Paul, and Mary and roughly on a par with Baez, but in terms of current trends he was in another class. He had originally been scheduled for Thursday night, but there were so many complaints from fans who could not make that first show that he and Baez were switched, with her on Thursday and him on the final Sunday program.

In the legend of Newport 1965, Dylan’s Sunday night set was the culmination of a three-day battle between electric rebels and hidebound folk purists, and the opening volley was fired on Friday by the Paul Butterfield Blues Band.

To blues purists, the Chambers Brothers, Lightnin’ Hopkins—even, at a stretch, Bo Diddley and Chuck Berry—were authentic exponents of an ethnic folk culture, while Bloomfield, Butterfield, and Bishop, talented as they might be, were interpreters.

Lomax tried to push Grossman aside, or maybe it was Grossman who pushed Lomax. Either way, in seconds the portly prophet of tradition and the portly purveyor of mammon—“the two big bears,” in Maria Muldaur’s description—were throwing inept punches and rolling in the dust. “It was a perfect confrontation whose symbolism was lost on none of us,”

The audience has not heard their murmured interchange and waits quietly, then starts screaming and booing as Dylan unplugs his guitar and leaves the stage, followed by the other musicians. Yarrow steps to the microphone, still wearing his dark shades and looking tired and worried. The crowd is going wild. “Bobby was—” he begins, then pauses, summoning his resources: “Yes, he will do another tune, I’m sure, if you call him back.” Dylan’s set has lasted seventeen minutes, a bit over the normally allotted time, but included only three songs and a lot of dead space, and the crowd is full of people who came to Newport specifically to see him. There is no way they are going to let him get away that easily, and they meet Yarrow’s challenge with a frenzied mix of boos, applause, whistles, and shouts of “More!”

Whatever one’s opinion, the naysayers have some facts on their side: The band was underrehearsed, and even if one thinks the first two songs sound great, “Phantom Engineer” was a high-energy train wreck. Aside from the music, Dylan’s performance was halting and disorganized, and he made no attempt to engage with the audience, to excuse the problems, or to distract from the confusion. His set lasted roughly thirty-five minutes, longer than anyone else’s that night, but that included two minutes when he was offstage and eight when he was onstage tuning, waiting for the other guys to get ready, waiting for a new guitar, a capo, a harmonica, looking back over his shoulder, complaining, or simply strumming disjointedly and playing an occasional note on the harmonica.

Dylan told Anthony Scaduto, “I did not have tears in my eyes. I was just stunned and probably a little drunk.”

Phil Ochs gleefully suggested that the next year’s finale should “feature a Radio City Music Hall Rockette routine including janitors, drunken sailors, town prostitutes, clergy of all denominations, sanitation engineers, small time Rhode Island politicians, and a bewildered cab driver,” backed by “the beloved Mississippi John Hurt’s new electric band consisting of Skip James on bass, Son House on drums and Elizabeth Cotton on vibes being hissed and booed by the now neurotic ethnic enthusiasts.”

Seeger did not come to the party, but the following morning a young folk fan was eating breakfast at the Viking and noticed him sitting with his father, Charles, at the next table. “He was telling his father, who was hard of hearing, about what had happened and what he thought of Dylan, and he sort of leaned over, and these were his exact words: ‘I thought he had so much promise.’”

During the intermission that night, Theodore Bikel put it in a nutshell, telling a Broadside writer: “You don’t whistle in church—you don’t play rock and roll at a folk festival.” For that analogy to hold, Newport had to be the church: the quiet, respectable place where nice people knew how to act. Pete Seeger was the parson. The troubled fans were the decent, upstanding members of the community. And Dylan was the rebellious young man who whistled. Which was exactly what he had always been, and what Seeger had been, and what Newport had celebrated.

“The people” so loved by Pete Seeger are the mob so hated by Dylan. In the face of violence he has chosen to preserve himself alone. . . . And he defies everyone else to have the courage to be as alone, as unconnected, as unfeeling toward others, as he.

At the Philadelphia Folk Festival a few weeks later, Phil Ochs sang his attack on wishy-washy centrists, “Love Me, I’m a Liberal,” then pointed to a stream of water near the stage and said, “If Pete Seeger were here, he’d walk on it.” There was irony in these attacks, since Seeger remained a red-tainted pariah to conservatives and was barred from mainstream venues where Dylan and Ochs were welcome.

“Eve” was joined by dozens of discs with socially relevant themes, often set off with rudimentary harmonica fills.

Collins cut a Kooper-backed single of Dylan’s “I’ll Keep It with Mine”; Albert

Their caressing harmonies were a much easier sell than Dylan’s quirky rasp, and through the rest of the 1960s, while his albums sold in the mid-hundreds of thousands and the Rolling Stones only once cracked the million mark, each Simon and Garfunkel LP sold at least two or three million.

Some old-time Village regulars tried to hop the folk-rock train, but the main lesson most learned was that they were not Dylan.

The other reaction, which was even more damaging, was, “I’m gonna be next. All I have to do is find the right agent, the right record company, the right connections, and I can be another Bob Dylan!” Yeah, sure you could. All you had to do was write “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall”—for the first time. That was what Bobby did, and none of the rest of us did that. Even if everyone didn’t admit it, we all knew that he was the most talented of us.

Around the same time he told Robert Shelton, “My idea of a folk song is Jeannie Robertson or Dock Boggs. Call it historical-traditional music.” For him, folk songs were not mellow, feel-good music; they were a connection to a tangled, mythic past. “It comes about from legends, bibles, plagues,” he told Hentoff. “All these songs about roses growing out of people’s brains and lovers who are really geese and swans that turn into angels.” And, he added: “They’re not going to die.” Twenty years later he was still drawing that line: “Nowadays you go to see a folk singer—what’s the folk singer doin’? He’s singin’ all his own songs. That ain’t no folk singer. Folk singers sing those old folk songs, ballads.”

For northern liberals, Vietnam was a much more divisive issue than voting rights and integrated drinking fountains, and many supported Johnson’s effort to stem the spread of international Communism. Then,

On tour with Baez in 1963, he had been refused a hotel room because of his unkempt appearance and responded by composing “When the Ship Comes In.” The image was from Brecht’s “Pirate Jenny,” in which a hotel maid dreams of a ship of avenging pirates who will sweep ashore and slaughter the complacent, respectable bourgeoisie.

He released Bringing It All Back Home in the spring of 1965, Highway 61 Revisited that summer, and Blonde on Blonde a year later.

Dylan’s reception at Newport had so much resonance because he mattered to his audience in a way pop music had never mattered before, and the power of that message came not only from Dylan but from Newport, from the fact that he was booed at a beloved and respected musical gathering, by an audience of serious, committed young adults. The fans who booed him from Forest Hills to the Manchester Free Trade Hall over the next year were showing not only their anger at his capitulation to the mainstream but their solidarity with that first mythically angered cohort of true believers.

Inevitably, though, the technology made a difference: at Newport the audience was full of people with their own guitars and banjos, and when the official program was over the unofficial music-making continued, sounding very similar to what was happening onstage. Electric instruments, for better or worse, demanded amplifiers and electrical outlets and established a divide: players behind the amps, listeners in front. It was not impossible to sing along with a rock band, but it was irrelevant. As Dylan put it, Seeger made his listeners “feel like they matter and make sense to themselves and feel like they’re contributing to something,” while listening to a rock band “is like being a spectator at a football game. Pete is almost like a tribal medicine man, in the true sense of the word. Rock ’n’ roll performers aren’t. They’re just kind of working out other people’s fantasies.”

“Dylan is no apostle of the electronic age. Rather, he is a fifth-columnist from the past.”

-

Car buying advice to my future self

I wrote this out in an online debate – preserved here for posterity

The main reason IMO for buying new, for me – (note, I’m assuming you’re doing to hold the car for ten years) when combined with the option of non-seller financing (and also paying cash if possible) is that it allows you follow a strategy where you maximize your bargaining position.

- Determine the car you want, do basic research and test drive without buying

- Call every dealership in a 100 mile radius asking for their “Best Price”, and asking them to call you back – tell them that you have financing and can buy immediately

- Not many will call you back, but of those that do get their best price if not financed with them and their best price if financed with them (David is very right about them selling the loan more than the car)

- Haggle as best as possible on the price of the car and the trade-in – be prepared to walk away

- Profit/Savings

Note, that most of the work is done before you step on the lot to buy the car. Also that you’ve reduced as many thing as possible to a fungible category, namely the car (every new car of the same model is the same), and the APR. You’re also attracting motivated sellers much more so than if you just walk onto the lot and start negotiating then.

That’s how I do it anyway

Note – step 2 is doing most of the work in the entire process

-

Rest in Peace Daisy

We got her on December 19, 2019 and she passed away at Treehouse Animal Hospital today (07/17/2025) slightly before noon. She was one year old when we first brought her home, just before Covid struck. She was an English Pointer, or so we were told. She did point birds for the first couple years of her life but she stopped when she was about 3 years old.

We could not have asked for a better dog – though she never learned to leash walk well, and flat out refused to come when called, no matter what we did, she had a wonderful personality and was a beloved member of the family and the perfect companion. She was always there during the hard times and her presence helped all three of us get through them. It sounds silly to write that, but it’s quite true. Her personality was perfect for the three of us. We loved her and she loved us. She was also the rare 60 lb lap dog and was always cuddling up to one or more of us.

She was a wonderful sister to Gizmo, they could and did play together for hours and usually stayed within five feet of each other at all times.

She was a wonderful companion to Marleigh – they took great delight in looking after each other.

She was diagnosed with a small cell sarcoma on her right leg in February of this year (2025). That manifested in a large lump on her right hip. Several vet visits later the tumor was proven to be inoperable and she was given four months to live.

She made it five.

Making the decision to have her put to sleep was quite difficult but I think we got the timing perfect. Her spirits were still good, and she did not seem to be in any pain, but her tumor ruptured yesterday and it was only a matter of time before that started to have effects

She went very peacefully. At Treehouse Animal Hospital they have an interesting policy of “no dog should go to heaven without tasting chocolate” and they gave her four Hershey’s Kisses, which Daisy enjoyed greatly.

The good people of Treehouse could not have been better. I cannot recommend them highly enough.

Today is a hard day, but as the day passes I’m appreciating more and more what a wonderful companion and member of the family she was and how much I’ll miss her and will treasure her memory.

Gizmo and Snow are quite depressed today – dogs really do seem to know when a dog has gone temporarily and when a dog is gone for good.

There are many stories I could relate here, the times she got into this or that, or the time she spotted a scorpion in a rental cabin and carefully followed it until I could deal with it, but there’s just too many to go into.

Goodbye for now Daisy – we’ll meet again sometime in a better world.

One more photo

We’ll miss you girl.

-

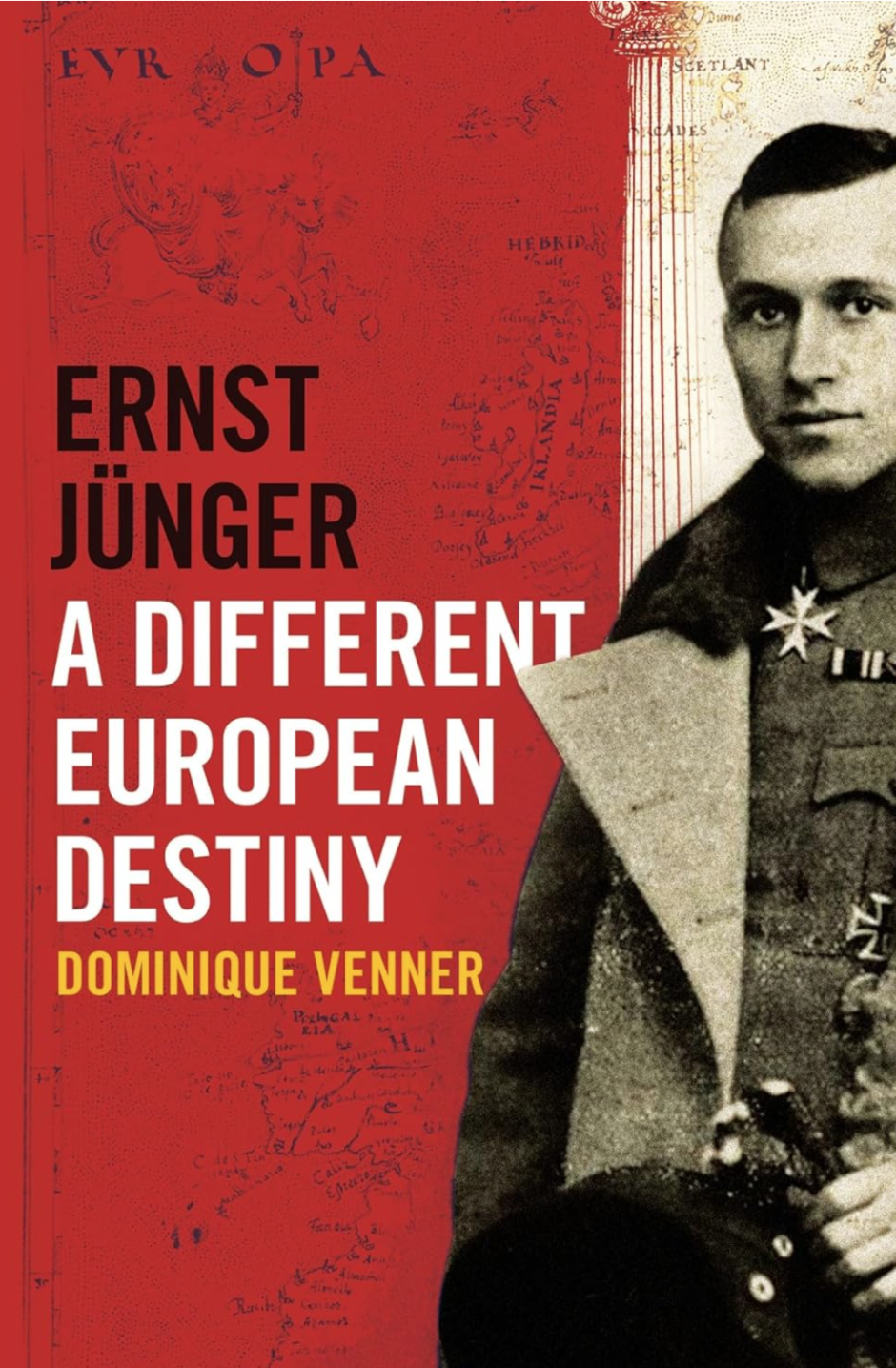

Ernst Jünger — A Different European Destiny

A peculiar book by a peculiar author about a peculiar man. I’ve been fascinated by Junger since I read Storm of Steel, and then his various sci fi books.

The author of the book was a certifiable, and apparently jailable, odious nutcase. Feel free to google him for more info.

It succeeds fairly well as a biography in that, after reading the book I don’t have anywhere near as many questions about the subject as I had before reading the book. His post WW2 experiences did not interest the author that much so that period is not covered as closely. The between the wars era is covered quite thoroughly.

Junger seemed to settle somewhere in the very small far right pro Jewish anti Hitler slice of German political opinion. Junger’s primary motivations were the thought of German people living under non German rule. I guess this book was a good reminder that politics, and political leaders are differing things to differing people in differing places, certainly initially.

Things of particular interest

- He edited things into and out of Storm of Steel with each version – mostly to take away any propaganda value to the Nazis.

- Despite being vocally and publicly anti-Hitler he had his fans as a writer in the 3rd Reich, and got some protection from them, including Hitler (life is strange)

- The range of opinion in the Weimar Republic was quite large

- The Weimar era was probably the only time in history where one could just summon thousands of people for street fighting in some sort of organized fashion

- The notion of a European identity, distinct from both race and America comes into form, mostly from the author of the book and not the subject. As an American I felt a sense of smug superiority after reading over the European complaints.

Reading a book by a foreign author aimed at a foreign readership was an interesting thing – there were numerous comparisons and examples that would be obvious were I raised in France

Not a perfect book but to fill in some of the missing gaps, particularly the sci fi era, but it’s worth reading if you’re a Junger fan (there’s not much else out there on him).

Quotes

An essayist, a poet, and the author of numerous works, Friedrich Georg (1898–1977) would, to the end of his days, maintain a close relationship with his elder brother, thanks to their intimate intellectual complicity.

Though, at their mother’s request, the children were indeed baptised, they would not receive any religious education, thus fulfilling the wishes of their father, who was unwaveringly rationalistic.

Just like Goethe, his father felt sympathy for the French and made certain that Ernst learned their language. He even organised for him a language stay with a French family, at a time when Ernst was still very young.

Indeed, Ernst seemed to be the very embodiment of those imaginative and talented duffers who, ever impervious to mathematics yet passionate about literature, prove to be full-blooded authors.

After three weeks, he felt smothered by despair. With an older comrade, he proceeded to desert the Legion so as to reach the Africa that the walls of the barracks had kept hidden from him. The two fugitives would be promptly brought back by the natives, who received a bounty for this type of work. Ernst thus found himself locked up in the regimental prison of Bel-Abbès.

Patriotic passions set Germany and all other European countries ablaze. Ernst Jünger and his brother Friedrich Georg rushed to be enlisted. On the third day of the war, they were incorporated into the 73rd Hanoverian Rifle Regiment,

Nearly a century later, a century that seems to have flown by in the blink of an eye, the stories told by those who witnessed the Great War are now many. None, however, could ever compare to the accounts given by Lieutenant Jünger. Beyond the obvious stylistic qualities, what is most striking about this young man is that although war did not spare him in any way, his descriptions are characterised by a staggering absence of complaints, compassion or moral judgement. In his accounts, life and death, laughter and suffering are intermingled. One thus draws from them a deep feeling of serenity and peace, despite all the fury of action.

Convalescing in the family home in Hanover, Lieutenant Jünger begins to carry out the formatting of the sixteen notebooks in which he had, on a daily basis, noted his memories of the great ordeal. Casting his eye over those notes, his father displays great enthusiasm. Convinced of the exceptional quality of his son’s testimony, he offers to publish it all himself. As regards the publisher’s name, it would be that of the gardener, Robert Meier.26 With Stendhal’s The Red and the Black in mind, Ernst, for his part, initially considers titling his book The Red and the Grey, the latter being the colour of the German field uniform. Soon, however, his recollections of ancient Icelandic sagas would inspire him to opt for the highly evocative title of In Stahlgewittern (Storm of Steel).

There is no doubt that Jünger was a born writer or almost, but it was the war that offered him the opportunity to open his mind to things and reveal the gifts he bore within.

Written, for the most part, in chronological order, it does not mention any dates, and the reader is often at a loss to put a date, even an approximate one, to the events and circumstances reported by the author. Jünger himself would not withhold the fact that, to him, the literary concern of the artist prevails over the memoirist’s concern for accuracy. As much out of modesty as for the sake of keeping a certain distance, the author deliberately redacted from his journals all exceedingly personal notes that were present in his original notebooks.27 For instance, he erased any mention of his relationships with women almost completely.

Such comments would be deleted in Storm of Steel, where the author takes on the appearance of a model officer, an officer who, in the truthfulness of the original notebooks, wondered at times when ‘this shitty war’ would end.

In the eyes of certain commentators, this rewriting of Jünger’s journals would raise the question of their authenticity. I consider this to be a fake issue, since the author is not a high-ranking actor in the war whose decisions or thoughts have a historical impact, but merely an insignificant witness to an immense tragedy.

Following Hitler’s rise to power in 1933, Jünger would delete all political comments so as to prevent any exploitation at the hands of the new regime’s propaganda. As pointed out by Hervier, the editions that came out after 1934 are thus paradoxically closer to the 1920 and 1922 editions than to the one published in 1924.30

Unlike so many other Germans of his generation, Ernst Jünger was not demobilised after the defeat of November 1918. Nor did he participate in the turbulent adventures of the Free Corps. What was left of the old army did not want to let go of such a promising young officer. In the defeated and chaotic Germany of the 1920s, infantry Lieutenant Jünger would punctually take up his service every morning at the Reichswehr barracks in Hanover.

What Ernst Jünger would retain from Hölderlin’s poetry is the impression that the human adventure takes place in a world whose meaning remains hidden. Thanks to art, however, it is indeed possible to decipher it. Art, in fact, allows us to sense the mysterious universal order that embraces men instead of rejecting them;

At the time, the author was no longer part of the Reichswehr, having been discharged on 31 August 1923.

On the contrary, what we encounter is evident esteem and even sympathy for those whom Jünger had fought against with unbridled fury. The reason is not that he could ever doubt his own rights, even for a single moment– that is not the issue here. Indeed, going back thirty centuries to reconnect with the ethos of the Iliad, he is willing to acknowledge the fact that his adversary is also within his rights. The actions of a Frenchman who kills a German in the name of his French fatherland are as justified as those of a German who kills a Frenchman in the name of the German fatherland. Each of the two armies is within its right. When one understands this, ‘one honours heroism; one honours it everywhere and above all among the ranks of one’s enemy.’

There is no eternal rest. There is only eternal movement that presses every smallest particle into its service.

In both Moscow and Rome, in Warsaw as well as in Berlin, the war had indeed given rise to a new type of man that supplanted the futile phrasemongers of the previous era: men who, in the words of Nikolai Berdyaev, are inclined ‘to transpose military methods to the very structure of life, practicing methodical coercion — a type of human that is fond of power and mindful of force and that manifested himself in both communism and fascism.’

On the evening of 9 November 1918, at a time when Wilhelm II had made the decision to seek refuge in the Netherlands, Berlin and the other major cities fell prey to the outbreak of Spartacist riots, that is, to the German version of Bolshevism, which had triumphed in Russia a year earlier. In Moscow, Lenin was convinced that the red revolution would extend to Germany. And it would indeed prove to be a very close call. The ultimate failure of this revolutionary project was due to the agreement sealed by socialist minister Noske with the Freikorps, an unforeseen phenomenon that had arisen from the chaos and rubble of the former imperial army. Against all expectations, the latter would reap success in Germany, while their equivalent counterparts, the ‘White Guards’, failed in Russia.

On two occasions, in December 1918 and January 1919, they would reclaim Berlin before intervening throughout the Reich to crush the red uprisings. This would be achieved by means of cannon fire and machine guns, with hundreds of deaths and quite a few atrocities perpetrated by each side. For a long time, Germany thus found itself in an endemic state of civil war. The final act of this era of armed unrest would be the Munich Putsch on 9 November 1923, which would throw a spotlight on Adolf Hitler’s name.

The myth of the eternal return reinforces a cyclical vision of history that is in radical opposition to the linear and finalistic viewpoint that results from Christianity and which the Enlightenment proceeded to secularise.

As for conservatism, and contrary to its French meaning, it suggests neither immobility nor attachment to deciduous forms. In the mindset of German romanticism, it represents, in fact, man’s awareness of the permanent and the essential, of all that resists time and that a revolutionary impulse will be able to free from any and all outdated forms. This notion of a revolution that would ensure the resurgence of a fundamental kind of order is a bearer of great dynamism. It rests upon the metaphysical conviction that the epoch in question is that of an interregnum that lies between an already dead order and another yet to come, a sort of ‘zero point’, as Jünger would say, starting from which everything becomes possible.

Owing to his temperament, furthermore, he was a doctrinarian, which Jünger was not in any way.

Within their own generation, the men that were thus moulded constitute an active minority that was not overwhelmed by the ordeal. In this generation, the fundamental bourgeois aspiration for comfort, hedonism and security simply crumbled.

Between 1914 and 1923, tens of thousands of young men acquired a taste for a type of existence wherein one’s indulging in risk led them to despise individualism and well-being both as values and as ultimate ends. To borrow some of Jünger’s words, these youths belonged to a race whose members ‘can gladly be blown up and still perceive the event as a confirmation of order’.

In Germany, the borders that delineate people’s feelings towards Russia coincide with the very ancient, cultural and historical border of the Limes and the Main. It divides Germany in two: a predominantly Catholic Germany, that of the South-West, which was subjected to Roman and Catholic influence; and another, that of the North-East, which evaded it. The former is associated with the Austro-Hungarian monarchy and was often at odds with Russia, with the latter acting as heir to the Prussian and Lutheran tradition and frequently seeking an alliance with Russia.

Unlike Napoleon or Hitler, who were both from the south of Europe and had fed upon imperialist traditions originating from Rome or Habsburg, no Prussian statesman ever fell into the trap of attempting to conquer Russia’s vast expanses.

Indeed, positions were rarely immutable. Socialists would rally around nationalism, and nationalists would sometimes join communism without betraying any of their profound convictions.

To those close to the National Bolshevik movement, Russian communism was only superficially Marxist in nature. It seemed to be, above all, a Russian phenomenon,

The appeal exerted by the ‘romanticism of the abyss’ is, as a rule, very foreign to Prussian coldness.

However, what would ultimately turn him into the most prominent author of the revolutionary Right was his rather fiery collaboration with Die Standarte (The Banner), a newspaper launched in June 1925.

In 1929, as part of the first version of his Adventurous Heart, he had already clearly distanced himself from all collective action.

In accordance with a phrase used within certain officer circles, nationalism would be experienced as one’s ‘altruistic duty towards the Reich’ and socialism as one’s ‘altruistic duty towards the people’. The only clearly designated adversary is the ‘bourgeois’, the focus of the author’s condemnation in The Worker (1932).

After 1927, however, one would notice a significant evolution in some of Jünger’s writings, a detachment that would have been unthinkable a year earlier. His artistic temperament would thus visibly take priority over political polemics, which was in contrast with his very nature.

Ernst von Salomon’s testimony highlights all that sets Jünger apart from the other authors of the nationalist movement. Jünger’s 1923 novella entitled Sturm had already heralded this distancing, which would be even more palpable in his political-literary work The Adventurous Heart, published in 1929. What one notices in it is a deliberate contrast between the passages dedicated to the martial fury of combat and others that display cold artistic distancing. He thus visibly cultivates a tendency towards egotism that one could never imagine in a political actor.

The French suddenly discovered that they were no longer the ‘Great Nation’ of yesteryear. They thus became resentful and surrendered to an inexpiable hatred for the Germans, revealing their own decline. Thus was modern nationalism born, the offspring of Jacobin passions, Boulangism and ‘revenge’. Through a reciprocal sort of movement, the demons of Pan-Germanism would awake in Germany.

the Germans saw themselves, by contrast, as the defenders of art against intellectualism and of authentic culture against the cosmopolitanism and artificiality that they deemed characteristic of France.

And it wasn’t a mere speech he was giving, for he embodied a manifestation of the elemental, and I had just been swept away by it.

From the very outset, a connection seemed to have been established between the still little-known young leader and the young combatant made famous by the publication of Storm of Steel. Hitler had also been a valiant WWI soldier, albeit a less prestigious one. He would thus send Jünger the first edition of Mein Kampf, dedication included. By return of post, Jünger would thank him by sending him his own war books. On the cover page of Fire and Blood, he inscribed the following tribute dated 9 January 1926: ‘To Adolf Hitler, the Führer of the Nation! Ernst Jünger.’

The following year, in 1927, Hitler offers Jünger a mandate to become a member of the Reichstag. The offer is turned down, for as Jünger would later state, to him, ‘the writing of a single verse was of more interest than the representation of 60,000 imbeciles in the Parliament’. Much later, on the eve of his hundredth birthday, he would respond to a journalist by adding with an ironic smile: ‘Later on, however, I would have equally rejected a similar offer from our highly esteemed Federal Republic had I been made one.’

despite the article published in Die Kommenden, the former officer had already distanced himself from political action by and large. There are multiple reasons for this. During the year of 1929, he published the first version of his work entitled The Adventurous Heart. This marks a certain break with his previous writings and a clear withdrawal into the inner sphere of reflection, that of more or less fantastical dreams and a writer’s formal concerns.

A careful reading reveals, however, that the writer did not sever his ties to the combative spirit of the previous years: he had only stopped believing in the resources of collective action: Nowadays, one cannot labour for Germany as a society; indeed, this must be done in solitude, just like a man who opens a breach in a virgin forest, sustained by the only hope that, somewhere, among the thickets, others are engaged in the same task.

One of the little-known reasons behind the success of the National Socialist Party lay in the unexpected support it had received from the female electorate, whose members had apparently been seduced by its promises of security and family policies.

Meeting Ernst von Salomon in 1929, he says to him: ‘I have chosen a high observation post from where I can watch the bedbugs devour each other’.

In other words, freedom is not a metaphysical idea. Jünger and the Germans do not believe in freedom per se, but in freedom as a function, such as the freedom of a given force. This idea is the very opposite of the notion of ‘cunning vote collectors’ and ‘freedom merchants’. The latter are ‘prisoners of the moral scheme of a corrupt Christianity that transposes the biblical curse to the worldly relationship between the exploiters and the exploited […]. They thus prove themselves incapable of envisioning freedom under any other terms than one’s deliverance from a certain evil.’ (pp. 99–100).

So what is Prussia? ‘Prussia is not a nation; it is the unadulterated and serious face of life.’

A State conceived of as being a chivalric order; to be free and to serve: the Prussian notion of State cannot be summarised more accurately than this. According to Spengler, it was the Prussian army itself, that of Frederick the Great; of Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, of Moltke the Elder and the old Marshal von Hindenburg that had embodied this very notion.

This idea is in sharp contrast to the specifically Hitlerian conception of race.

His racism owes nothing to the writings of someone like Gobineau.119 His true master was the author of On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, albeit in the latter’s simplified formulation spread by popularisers at the time of Hitler’s youth.

Ernst Jünger had sensed that, just like Marxism, Hitlerism was a distortion of Enlightenment rationalism, a sort of madness-afflicted reasoning. Hitler believed himself to have discovered the secret of the ideal City based on science and reason. What had once been experienced as immemorial, accommodating and flexible wisdom would be imposed with geometric rigour by a dictatorial law that would enact thorough and tyrannical rules to be enforced by legions of obedient and narrow-minded officials. This distortion of reason, it must be said, is not specific to ‘totalitarianism’. Indeed, most modern societies have fallen prey to it, under the pretext of hyper-rationality and submission to the judgements passed by ‘experts’ and ‘specialists’.

Very present in The Worker as part of the author’s response to the challenges of technological domination, the attitude of ‘heroic realism’ would subsequently disappear from Jünger’s mental universe, once his mind had undergone the great ‘humanist’ reversal heralded by the publication of On the Marble Cliffs in 1939.

The ‘elemental’ is to be understood as the instinctive forces of life, which are stifled by rationalism and the bourgeois rule.

In it, von Trotha criticised Jünger for his ‘fundamentally individualistic attitude’ and concluded by stating that by authoring such a book, Jünger was getting dangerously close to ‘being shot in the back of the neck’. One wonders what could have justified such a threat. The explanation would soon be given. Jünger, continues Trotha, ‘disregards the fundamental question of blood and soil’. Indeed, nowhere in Jünger’s work does one find a single trace of the racial Darwinism that characterises Hitlerian National Socialism. Additionally, nowhere in this cryptic book of his are the party and its leader mentioned or even hinted at, although they were already marching towards power.

Although basically retired from politics, Jünger chooses his side: that of Prussia and the Reichswehr, against National Socialism.

And yet, those of us who study history in a desire to elucidate its mysteries can readily interpret the writer’s motivations. Indeed, everything points to the fact that what he favoured was a revolution from above, in accordance with the Bismarckian model. A total revolution, as heralded by his writings, but a controlled and regulated one, a new and enlightened sort of despotism.

he is targeted with a first raid in April 1933, initiated by the subordinates of the local police amidst the climate of general suspicion and latent civil war that characterised the first months of the new regime.

Over the following years, Jünger would never relinquish his increasingly greater reservations, while still refusing to emigrate and sever his ties to his own homeland. Opting for inner exile, he devotes himself to his entomological work and to penning texts that are truly timeless, until the publication, in September 1939, of his novel On the Marble Cliffs. The work is immediately perceived as a coded condemnation of the regime. He is denounced accordingly to Hitler himself by Reichsleiter Philipp Bouhler (1899–1945), the head of the ‘Party’s Control Commission for the Protection of National Socialist Writings’. Harbouring respect for the heroic soldier of the Great War that authored Storm of Steel, Hitler would, however, prohibit all persecution: ‘No one touches Jünger!’

In response to the pleas made to him, he would dryly reply, ‘There is no room for me in an army where Göring is a general.’

Indirectly involved in the plot of 20 July 1944, he evades the fate of a great many other officers. During a long life in which he would also experience other, less dramatic developments, he had overcome many a mortal peril while enjoying a strange privilege of invulnerability.

To put it very simply, the purge, which also targeted right-wing opponents, was the result of a manipulative plan hatched by the leaders of the Reichswehr, who wanted to neutralise the now troublesome SA.141 For once, they had enjoyed the complicity of some of the highest-standing party leaders, namely Göring, Goebbels and Himmler, who also wanted to bring the all too independent SA back in line by eliminating its leaders.

As soon as Hitler took power in 1933, Jünger, Spengler, von Salomon and many other major authors of the Conservative Revolution became his virtual opponents. The new regime seemed to them a mere travesty of the authentic ‘national socialism’ they wished for. In accordance with the excellent thought expressed by the historian Ernst Nolte, ‘“national socialism” was not, until 1934, a protected trademark’.

One had better be wary, therefore, of placing their entire trust in all that has been written in the aftermath of 1945, as memories do tend to undergo the occasional obscuration. It is not that the actual honesty of the witnesses should necessarily be called into question, but what was clear before 1945 might no longer be so afterwards. This is because the unconscious part of one’s memory will always engage in a selective sifting process, especially among intellectuals, who are naturally tempted to add coherence to their past conduct in light of newly acquired principles.

No one could thus have foreseen a future that had no precedent.